I’ve been in the NFT space since the pandemic, but most of my friends aren’t into crypto and the idea of buying digital art. So, over the last year, as the market has taken a hit, I’ve gotten this question a lot.

“So… what’s up with NFTs?”

Which, is code for, “That was a weird fad, wasn’t it?” or, “You were definitely, totally, wrong about those!”

I can’t help but laugh. This is certainly the time for nonbelievers to gloat. An unrelenting bear market, the SBF FTX scandal, and the watchful eye of the SEC have chilled much of the activity around NFTs. With prominent projects pausing due to “market volatility,” celebrities getting sued for promoting Bored Apes, and porous infrastructure ripe for scamming, Web3’s1 foundation is getting rocked.

I’m optimistic on the tech, however, when I meet with the studios, institutions, and global brands that are heavily investing into blockchain. When I discover artists creating and selling beautiful digital work, I’m reminded that this isn’t the end. It’s just the end of the beginning. Although I do agree with my friends that some elements of the modern NFT trend really are dead, we diverge at a crossroads. Web3 can keep going down this path, circulating NFTs amongst the same echo chamber of crypto whales and degen traders. I don’t think this necessarily means the end of NFTs, but I do think it may confine them to a niche bubble. Meanwhile, my sights are set on the track toward a more open and robust future for Web3.

To get there, we will need to revisit the existing paradigm for NFT growth: resale economics. And we will also need to reconsider why anyone would want to consume the product to begin with. It can’t just be about ETH profits, because once those dip, so goes the NFTs. It’s gotta be more than a purposeless shitcoin to pump and dump (the DeFi2 version of NFTs is currently playing out in front of our eyes).

NFTs in and of themselves can be tectonic, distributing power dynamics, repairing the consumer-purveyor relationship, even making consumption cleaner for the planet, but they have a serious branding and marketing problem. The answer isn’t re-packaging them with a less irritating name, procuring a movie star’s endorsement or convincing the doubters that they’ll get rich off them. Instead, we must tout the human inspiration, ingenuity, and invention that brought us here in the first place. We already know it’s gotta be about the art. But you can’t have art without the artists. If we respect both, then we can flourish in a healthier environment for all.

The Role of Resale Culture

The one thing that everybody seems to gloss over with NFTs is how fundamental resale is to their DNA. In that sense, they are patently distinct from classical art, fashion, and other collectibles. Their purpose – their identity – is in being resold for a profit. I saw it firsthand with our own collection, Adam Bomb Squad. Once we sold out of our first NFTs, most of our clothing community assumed we’d drop another set like a seasonal fashion collection. But the NFT business is based on reselling the same art repeatedly. Due to limited supply and a theoretically rising demand, the collector stands to make money by turning these NFTs over, and so do the creators as they receive “Creator Royalties” on every flip. On our OpenSea auction page, the first score reads that we’ve passed 22,542 ETH in trading volume. That’s over 37 million dollars. But we only made a fraction of that money. Most of that sum went to the traders.

Over the last generation, there’s been a shift in how consumers consider resale and pre-owned items. When I was growing up, there was a stigma around used cars, yard sale furniture, and Salvation Army clothing. With the advent of Craigslist and eBay, it was not only easier to shop for “vintage” goods, but it also became more fashionable. Purchasing someone else’s used product was eco-friendly. For the consumers, you could pay a premium and access a luxury item that had been hard to find or expensive. For the sellers, hawking pre-owned goods became a lucrative business. And that’s the thing – the buyers and the flippers became one and the same. Today, we’re all prosumers in the trading game.

The best illustration of this shift in consumer mindset comes via Supreme and sneakers. In the 2000s, it was a strange sight to see teenage hypebeasts camped out on Fairfax Ave. for special caps and shoes. Although kids lined up on the sidewalks to buy rare clothing for themselves, many capitalized on the supply-demand economics of scarce streetwear by buying extra items to sell on eBay. Sneaker resale stores like Flight Club and Stadium Goods opened in streetwear neighborhoods to accommodate collectors looking to offload their gains. And then apps and platforms like StockX expedited the process through online transactions.

NFTs – the profile-picture kind (the ones you’re thinking of – cartoon animals with interchangeable, Mr. Potato Head style traits) are the most hyper, extreme culmination of the decade-long reselling craze. While flipping Supreme and sneakers still integrates the manufacturing, shipping, and warehousing of a physical product, NFTs are JPEGs that are materially code on a blockchain. Now, buyers/sellers can complete art transactions with the click of a button. Money zips back and forth across the marketplaces at a frenetic, day trading pace, accelerating the growth (and the downfall) of digital collectibles thousandfold.

You can’t talk about the NFT phenomenon without mentioning the staggering prices some of these JPEGs commanded. But you can’t address the numbers without acknowledging the speculative trading and reselling that built the house. The question then becomes, “What are NFTs without the resale element?” And more importantly, “Can NFTs survive without high secondary market value?”

In a market where secondary sales on NFTs are collapsing and Creator Royalties are being suspended (again), these are questions we must answer in order for Web3 to have a viable future.

What are Creator Royalties?

For years, the golden promise of Web3 has been that there’s finally a mechanism whereby creators, founders, and entrepreneurs (hereafter referred to as Artists) can receive a cut of their secondary sales. Last week, OpenSea, the leading NFT marketplace, announced that they were “temporarily” cutting royalties for artists selling their work on their platform. As the NFT auction houses compete on this race to the bottom, undercutting each other to appease a limited number of wash-trading collectors, they threaten to bring down the entire ecosystem. “This move is part of a wider shift across Web3 — one that favors NFT collectors at the expense of creators.”3

Most NFT artists and projects sustain not only by minting out of their initial drop but pumping their work on the resale markets and drawing royalty checks. Royalties also incentivize the creators to keep adding value and “utility” to their work beyond the visual art. If royalties are shut off, the game is compromised. Not only will many of these artists and projects lose steam as their revenue dries up, the collectors and traders will also suffer because their NFTs will lose their luster at auction.

NFTs and Web3, like crypto surrounding them, are already on hard times compared to where they stood a year or two ago. OpenSea’s announcement sucked the last gasp of air from the room. To many, Creator Royalties are Web3’s founding premise and the linchpin holding the system together. The marketplaces’ reneging on their commitment to the artists could dispel the dream.

OpenSea first attempted to pull Creator Royalties in November (citing a loss of market share to other marketplaces who had broken the “golden promise”) but stopped when artists and the Web3 community banded together to voice their disapproval. At the time, many of us knew that it would only be a matter of time before they tried again. As much as I wanted to believe that these platforms have the artists’ best interests in mind, their priorities are surviving, maximizing profits, and keeping investors happy. As an NFT founder myself (that uses secondary profits to maintain the business), I was forced to plan for the abolition of artist royalties.

I wrote an essay (and a chapter in my forthcoming book) entitled “NFTs Are Forever” where I suggested a tenable future for a Web3 without Creator Royalties. “Instead of looking at mints as a one-and-done…what if a brand’s drops could be continuous and often?” If artists can’t make money off secondary sales, then maybe the approach should be more primary sales, just like traditional creators, consumer goods brands, and collectibles companies have always done. More artwork goes against the artificial scarcity model that traders believe boosts short-term resale value. What they neglect to see, however, is how more art serves the artists, which then trickles down to the collectors and community. Plus, how powerful brand-building can be in shaping long-term image and demand (Of course, many NFT collectors miss it. The fast, frenzied flipping makes it hard to look up. Good branding is all about time, discipline, and consistency, three of the rarest NFT traits that you can’t buy).4

Although Creator Royalties can be beneficial for artists — if marketplaces choose to honor them (and especially if NFT trading activity exists)—, what if it’s better for NFTs to not concern themselves with resale value? As I will propose, Creator Royalties may be to blame for some of Web3’s most vexing and dysfunctional issues. If they’re abolished, could it make for a more sustainable industry? Is it best for the well-being and productivity of the artists?

Where did Creator Royalties come from?

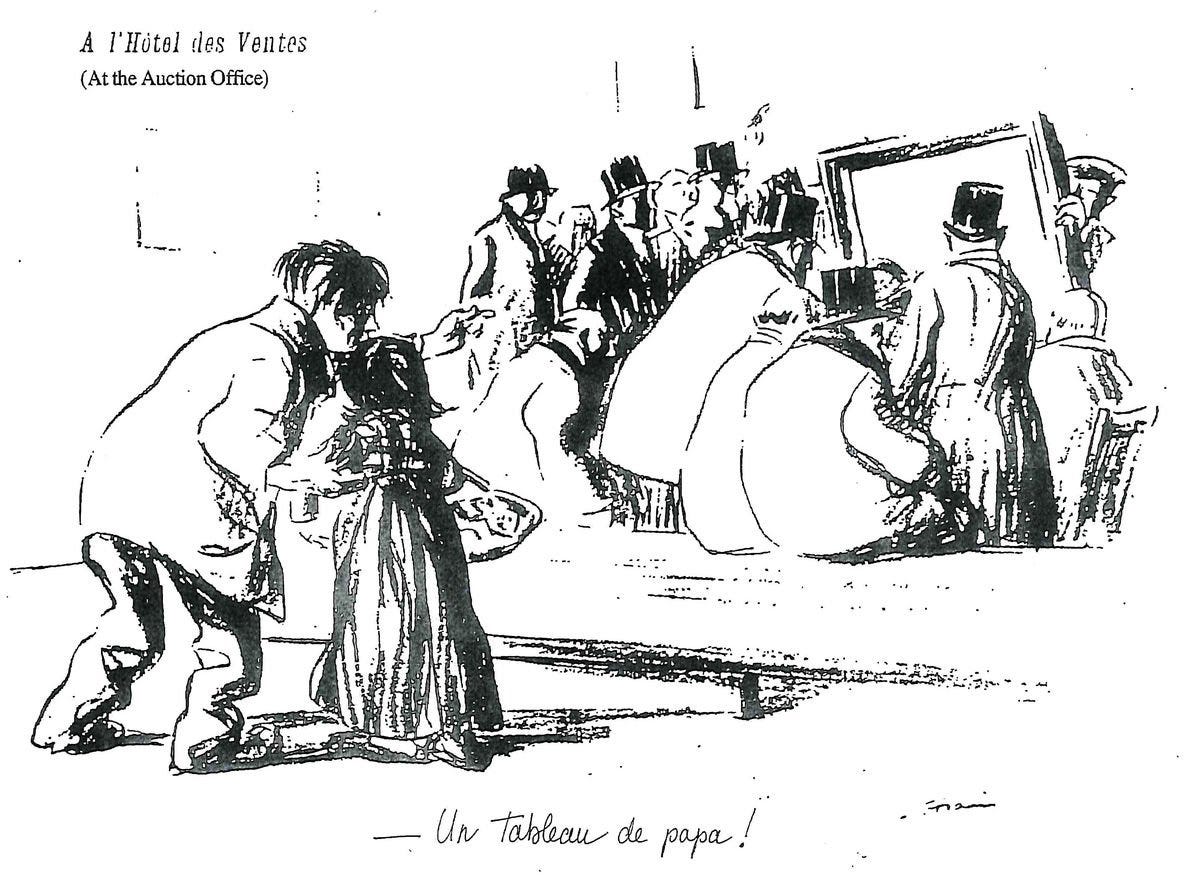

For centuries, if an Artist sold their work, they typically didn’t profit as it traded around the marketplace. Let’s say an Artist sells a painting for $500. If they do their job and their legacy unfolds successfully, that painting might fetch $500,000 at the auction house. Yet, the Artist won’t see any upside in that sale. Perhaps unfairly, the collector will win the biggest, followed by the auction house and the gallery that facilitated that transaction.

Artists have been trying to address this discrepancy for centuries. In 1889, the destitute family of French Realist painter Jean Francois Millet sat by and watched a copper magnate flip the artist’s “L’Angélus” for a record breaking 553,000 francs. In 1920, France was the first country to implement droit de suit (“the resale right”), spurred by a Jean-Louis Forain drawing of a beggar and his child outside an auction house where the father’s painting is being sold for large sums.

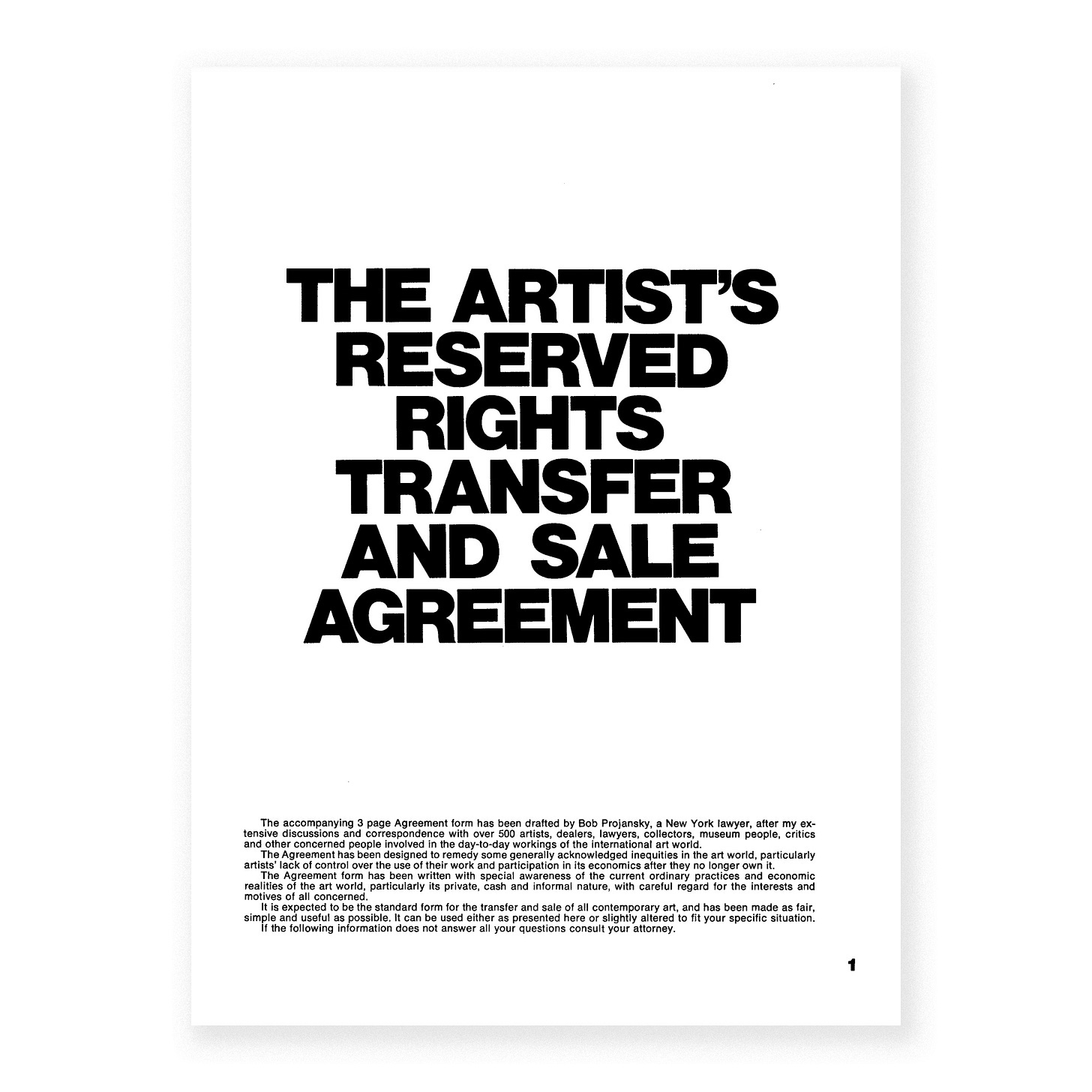

Today, over 70 countries have enacted ARR (Artist Resale Royalty) laws. The United States is not one of them, although there have been multiple attempts to implement some form of fairer agreement between art buyers and sellers. In 1971, art dealer Seth Siegelaub and lawyer Robert Projansky drew up The Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement to “remedy some generally acknowledged inequities in the art world, particularly artists lack of control over their work and participation in its economy after they no longer own it.” Enforcing the contract has been difficult, however, especially in the absence of a federal royalty statute. Only 31 states recognize the right for artists to receive royalties from their first sale, let alone their secondary sales. California is the only state to have achieved some type of droit de suit protection for artists, but that was struck down by the courts in recent years, signaling the end of the line for American ARR laws.

One of the most formidable opponents to artist royalties have been the auction houses themselves. In 2014, Sotheby’s and Christie’s fought against the American Royalties, Too (ACT) act. According to the New York Times, they spent over $1 million to lobby against artist royalties efforts. This is wild when you consider that out of $65 billion in global art sales annually, 26.3 billion came from auctions. “When most visual artists are only getting paid from the initial sale of their work, but resales represent 40% of the global market, shouldn’t they benefit from the secondary market as well?”5

This is why NFTs were so revolutionary for artists at the start of pandemic lockdown. In 2020, a group of cryptoartists signed a letter to the various NFT marketplaces, asking them to honor a 10% artist royalty on secondary sales. If everybody agreed to the social contract, this radical new technology could correct a centuries-old imbalance in the art market. “We, as a group of united cryptoartists, recognise a unique opportunity to chart a new course in the art world and improve conditions for all artists of today and tomorrow.” The plea – or demand – was buttressed by the argument that visual artists are just as much creators as musicians, authors, and playwrights, who all receive royalties for their work as it plays down the line.

What happened next made history. The marketplaces shook hands on this agreement and the modern NFT trend exploded. Through “smart contracts” (whereby you can track where the artwork moves), the marketplaces (the eBays and Depops of NFTs) started enforcing a royalty back to the Artist every time their art traded. NFTs caught on in early 2021 for a number of reasons, but the incentive was high for emerging creators and start-ups. Here was an equitable fix for the disparity in reselling dynamics. Here was a just shot at wealth creation and a chance for Artists to make as much as their resellers.

Creator Royalties became the heartbeat of NFTs. Not only were artists motivated to create by participation in the resale economy, but they were also protected by a system that respected their livelihood. And if the artists were honored and better incentivized, then the traders also benefited from their investment into the space. In a bull market, everybody from creators to collectors to marketplaces won: WAGMI (We’re All Gonna Make It). But, after a short, few months of crypto downturn, artists were quick to be blamed and trampled on.

To be fair, there were enough “rugpullers” who deserted their communities for the finger to point squarely at greedy founders. Because of the resale element and the “gratuity” of royalties, creators are expected to perpetually attend to their existing NFTs. If they don’t or are simply not doing a good enough job of hoisting a collection’s floor price, they are accused of scamming their community. You can see how this can quickly create a Spiderman blame game meme of resentment and confusion.

When resale gains become the driving reason to make, collect, and push NFTs (instead of being a bonus on top of culture, tech innovation, entertainment, hobby, identity, community, fashion, and most importantly, art), then NFTs become unmoored in times of financial crisis or crypto bear markets. We could learn from sneaker history. Every so often, the market wilts (as it’s doing now) because when it’s just about the money and there’s less spotlight on product, design, and storytelling, the sneaker becomes a variable. Sneaker flippers migrate to fine art, then watches, cars, and flipping homes. This happens every generation. Fortunately for shoe brands, their business is dependent on selling vs. reselling. In times of downed trading activity, they are better insulated from market forces since they never much interacted with them to begin with.

Can Creator Royalties be harmful?

Artists aren’t the only ones who stand to benefit from the notion of secondary royalties. As I mentioned at the outset, across other categories, sellers are making as much – if not more – than the makers. “82% of Americans, or 272 million people, buy or sell secondhand products… including electronics, furniture, home goods and sporting equipment.”6 There are even websites to flip popular restaurant reservations.

There’s no other sector that has been as impactful – and impacted – by reselling the way that fashion has. It started with used clothing shops. In the 19th century, the advent of mass production led to a surplus in product and introduced the idea of clothing as disposable. Thrift stores became a big business. At first, Christian ministries capitalized on the cheap clothing to fund their outreach programs. By the 1950s, wealthier shoppers developed a taste for vintage clothing and suddenly “thrift” went from shameful to cool.

Today, sneakerheads to The RealReal shoppers have redefined the fashion industry. In 2021, “recommerce” grew twice as fast as the broader retail market and is projected to bloom by 80% over the next five years to hit $289 billion. Case in point, Nike’s annual revenue was $50 billion last year, yet the sneaker resale market is currently estimated at $10 billion and expected to reach $30 billion by 2030. Every weekend, my son begs me to take him sneaker shopping at grey-market resale stores along Melrose and Fairfax, not to the mall Foot Locker or Nike.com. That means that the sneaker flippers are eating a significant chunk of the footwear giants’ pie.

But sportswear companies are slow to engage with the sneaker resale market.7 Although adidas only recently accepted that if they can’t beat ‘em, join’em, Nike disavows and even fights against resellers. Why? My theories: For one, there are securities regulations at play. Two, behind the scenes, the industry thinking is that the artist should remain pure and agnostic. Their role is to make great, unadulterated art, far from the seedy, speculative nature of gambling around their work. Their focus, instead, is on primary sales from replenished designs.

What makes NFTs so unique is that the system is centered on the artist profiting off resale of their work. Because of Creator Royalties, the artist not only acknowledges the secondary market on their artwork, but they are also actively involved in hyping up their piece, doing whatever they can to inflate its value at auction. But it complicates the artist’s purpose, if not presents a conflict of interest.

For one, if the artist is profiting off resale, then they need to provide something to warrant it. Although the artist believes that their original work is complete, the collectors don’t necessarily agree that they should be rewarded on secondary trades forever – especially since they were compensated for what they asked for at primary sale. Hence, the demand for artists to provide “utility” or added value to the art to pump its profile at market. This opens a dizzying trap where the artist is forever shackled to their initial collections, justifying their value and purpose to a customer for whom the NFT will never be enough (because the money can never be enough). This misalignment is frustrating for both parties. After the artist mints a collection, they are expected to promote and pimp that body of work for the rest of their lives, even if the original holder whom they made the promise to exits (even if a collector buys an NFT from a reseller for 10x the mint price and now expects 10x the utility from the creator!).

Most artists, however, aspire to be prolific and want to keep creating new work. In fact, as an artist myself, I can’t think of many creators who love revisiting their past output. Art is the act of improving upon, evolving, and closing in on a more perfect telling. Even for businesses and companies, to impede them from producing more designs would stymie progress, thwart innovation, and foil the very spirit of creation. It’s nearly impossible to forge a substantive brand story without adding pages to the book.

So, Creator Royalties aren’t better for artists?

Hypothetically, they are. But only if they pay artists better and more importantly, are helpful beyond just providing financial gain. Currently, the NFT model is governed by resale profits; that immobilizes artists, arrests productivity, and demeans the art. Plus, since most emerging artists don’t have high demand at the start of their career and may not see secondary activity on their work until they’ve built their repertoire, taxing the collectors can inadvertently hurt the creators’ bottom line in the long run.

Buyers can force retail prices down to compensate for the artist’s resale percentage later. Consider the latest NFT trend of affordably-priced Open Edition artwork by esteemed creators who are typically priced higher. These collections have been successful because of the chance of fatter margins at resale, but they could bruise the artist’s brand perception. It could be best for some artists to forego royalties to preserve their go-to market value. In 2018, Diddy purchased the artist Kerry James Marshall’s painting for $21.1 million at a Sotheby’s auction. Although controversial because Marshall didn’t see a penny from that sale, his asking price for original artwork remains high and respectable.

In the physical art world, the potential harm of Creator Royalties has already been researched and proven. In fact, the only artists who seem to make more money if royalties are implemented are *surprise* the top 1% (and dead artists). “The data shows that the likely beneficiaries in the resale market will be, almost exclusively, the super-stars of the art world. The other 99% of artists will be left out in the cold.”8 Andy Warhol’s estate wins biggest while not a single young, emerging artist receives a royalty in the data. Two years ago, in the NFT market, many budding creators were partaking in royalties but today, almost all the trading volume is dictated by a few “blue-chip” projects, with some of them sharing the same owners. The rich get richer, even when they’re the artists.

The Solution

Regardless, if Creator Royalties cease and secondary market volume continues to decline, the resale matter may be moot anyway. What an opportunity to reimagine how NFTs can not only survive, but thrive, under a different framework!

First, there must be a renewed focus on the artist. We seem to forget that without artists, there is no art. Artists must be given space to create. Entrepreneurs should be allowed to build. Founders need room to invent. They should also be encouraged to make whatever they want. We need to find better ways for artists to be paid off secondary sales, but first, we need to ensure they get paid for the work that they do and let the market determine the value.

Many digital collectibles over the last couple years were inflated (along with everything else in the economy). They were also appraised for their speculative trading price rather than what they actually offered. It’s critical that we give collectors reasons to buy NFTs beyond the promise of wealth. There’s nothing wrong with reselling, but until that moment, what non-financial value can an NFT bring to somebody’s life? NFTs can be a membership card to a club or a virtual extension of self-expression, identity, and fashion. NFTs can be a gaming asset or memorabilia associated with a popular franchise. Point being that there must be a tension between collecting the NFT and flipping it. For NFTs to be normalized, it’s essential that people want to keep them as opposed to looking for the fastest reason to dump them.

The harsh truth is that most people, many Web3 loyalists included, don’t respect digital collectibles the way that they do physical life product. This is nothing to be ashamed of, but it’s obvious from the way even the most diehard NFTers appeal for “real world” utility of their JPEGs, that they don’t sincerely believe NFTs are real. It makes sense. NFTs are so new that they haven’t accrued the time, storytelling, and memories to turn myth into fact. It took decades for retro sneakers to be treated as a status symbol. Japanese appreciation for vintage product, proliferation of hip-hop fashion, and ‘80s nostalgia turned old shoes into a hot commodity. Paintings are met with “My kid can paint that” before the right gallery cosigns the artist. Suddenly, the mainstream audience sees the art in a new light. Fashion trends are fabricated and imaginary until there’s mass adoption. Red Astro Boy boots and digital freckles are silly before they become a very meaningful and profitable business.

For NFTs to become “real,” they must be fostered by a vibrant culture and narrate a consistent brand. Relatively few projects in Web3 have the means and wherewithal to do this, but it’ll take a rising tide to lift all boats. Streetwear is mainstream fashion today, but it started with renegade artists around the world firing up T-shirt labels around their perspectives and lifestyles. Season after season, hoodie after hoodie, the brands’ discipline and passion for creating avant-garde product eventually convinced the masses that they were real. The prices for those shirts, meanwhile, organically increased in price, first in retail and then on the secondary market. $25 to $40 to $100 over a decade. At resale, today, coveted T-shirts can sell for thousands of dollars.

Because of the moody ups and downs of crypto, Web3 companies and NFT brands should also be stabilized by Web29 business in the physical world. It’s classic diversification. This piece was ignored while crypto was hot. It’s like running a business in the pandemic: it was hard to imagine that employees would return to the office one day or we’d ever mosh on top of each other at concerts again. Although Web3 first called for a total abdication of Web2, the NFT brands that will withstand crypto winters will be those that can sympathize with both worlds.

The End (of the Beginning)

I really hope that one day, the marketplaces honor Creators and Creator Royalties again. But I also think it’s unrealistic – and not the decentralized Web3 way – for artists to depend on profit-seeking corporations to sustain their careers.

I also believe that for NFTs to last, artists can’t be controlled by resellers and reselling. The flipper’s mindset is about harping on the past, but the artist’s job is to create the future. They should work in concert, with the trader’s purpose to curate and resell what exists, leveraged by the goodwill of the artist’s repertoire and legacy. This is where the value of the artist’s brand comes in. But, to develop a brand, artists must be allowed to consistently introduce new work into the market and tell a thoughtful, cohesive story over time. Only then, can a healthy secondary market take hold.

Currently, the NFT structure is lopsided, with an asymmetry between creator and collector, art and shitcoin, Web2 and Web3. All ingredients are needed in the recipe, but in equally apportioned amounts. I have faith that good ideas and great art will find their way through, as they always seem to do. But we’ll first have to say goodbye to the old way of doing things. NFTs are dead. Long live NFTS!

If you like this essay, don’t forget to pre-order my next book NFTS ARE A SCAM / NFTS ARE THE FUTURE, publishing through MCD/FSG Books and delivering to your door on May 16th, 2023. I’ve subtitled it “The Early Years” to chronicle the incredulous events, innovation, and drama that’s unwound in NFTs since 2020. This is a snapshot of who we are on the cusp of pandemic and post-pandemic, physical and digital, Web2 and Web3, and a hopeful message of where it can all lead. I’ve also included exclusive interviews with Gary Vaynerchuk, Steve Aoki, Gordon Goner (Yuga Labs), Betty (Deadfellaz), and Mel Tal (Nike, Rug Radio). As always, thanks for reading and for keeping an open mind.

Web3 is the next generation of the Internet comprised of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency and decentralization. Meanwhile, Web2 is the Internet we know today, characterized by social media and controlled by Big Tech platforms like Google and Meta.

Decentralized Finance is the crypto-centric financial model with no centralized authority to control operations.

In my opinion, this is why NFT collections are called “projects” instead of “brands.” The terminology exposes how experimental and ephemeral the space deems these ventures to be.

In this instance, I use “Web2” not in the tech, centralized sense, but in the non-crypto, non-NFT, physical world sense.

Comprehensive note as ever and much to think about - well done sir…

Having spent time in the dark rooms of china during the original ICO bubble, and helping artists mint their own NFTs as part of our FENIX ecosystem, it has certainly been something that I have watched closely over the last five years…

For what it’s worth, my belief is that your peer, Jeff Staple has come the closest I have seen to date to creating a sustainable NFT ecosystem, by creating genuine utility.

At the end of the day, an artists most valuable asset, which resale culture has effectively stolen from them sits around exclusivity and access and in that regard, NFTs feel like a perfect way for artists to be able to monetise. The stapleverse created three exclusive clubs through the minting process - feed, poop and pigeons and then underpinned that exclusivity by adding utility, real world and virtual, to each separate group… and that’s how value is maintained.

Interesting times ahead for sure…