Nike filed a trademark infringement lawsuit against A Bathing Ape last week and social media was ablaze. The fight is sensational because both brands are sportswear juggernauts, setting up a Batman vs. Superman of street fashion. It’s also fascinating because we prefer to believe that Nike and Bape play for the same team. It’s like watching Jordan and Pippen go at each other in a house divided. Of course, it’s gonna make headlines.

The most soap-operatic element of the legal battle, however, is that it feels so personal and familiar, like two of your closest friends in an argument. The thing that has historically set streetwear apart from other industries is how it’s spiritually framed around culture and community. Commerce is intrinsically entwined with artists and creators, to the point where corporations behave and present as humans. Collaborations have been resonant for this reason. The audience believes that the relationship is genuine, bridged by conversations. This is also why the design reaches further. It’s not a multinational enterprise like McDonald’s mass-producing your burger. The streetwear sandwich is handcrafted and personalized by food artisans, carefully executed and purposefully marketed (These are the myths we tell ourselves anyway).

Nike’s suit wasn’t entirely shocking. For the last few years, the Beaverton-based apparel giant has been taking action against brands that have been selling footwear that is inspired by – and arguably infringing upon – Nike’s most classic designs like the AF1, Dunk, and Jordan 1. Due to eased access to manufacturing facilities, stock molds and lower minimums on production orders, it’s become a trend for rappers, upstart designers, and renegade artists to customize their own twist on an iconic sneaker silhouette. Many of these defendants are younger, emerging designers like Warren Lotas, Kool Kiy, and John Geiger. Others are budding entrepreneurs and first-time footwear designers who are trying to distinguish themselves from being just another T-shirt brand.

Nike’s made a concerted and publicized effort to clamp the faucet on these types of products even though the defense has consistently been, “What about Bape?” After all, A Bathing Ape (the popular streetwear brand that was founded by Japanese designer NIGO and is now owned by Hong Kong’s I.T group) has been brazenly selling their “Bape Sta” AF1 ripoff for twenty years now. Many of us always wondered how they were getting away with it. There had to be some sort of back-channel agreement considering NIGO’s influence on the culture and social relationships between the two entities. Back then, that’s how everything seemed to work in this enclave community. Regardless, it seems like that handshake has now collapsed.

The noise around the Nike-Bape suit is just another PR strike against the Swoosh in recent times. Just this past week, artist Joshua Vides printed “FUCK NIKE” T-shirts after accusing the corporation of stealing from himself and other artists. Mike Cherman, founder of MARKET, designed a graphic calling out the hypocrisy of Nike suing other designers when their first design, the Cortez, was modeled after Ontisuka Tiger. Nike’s taken the foot off culture-based energy marketing and has weathered its share of internal hiccups. In the midst of the MeToo movement in 2018, at least 11 male executives exited after a women-led “revolt,” followed by claims of gender pay gaps and a boys club work environment. And then there was that reseller scandal where VP Ann Hebert resigned after her teenage son posted photos in front of walls of Nike boxes that inventoried his sneaker-flipping business.

It’s hard to say whether the bad vibes have affected business or if Kanye’s adidas run in the mid-2010s slowed the Nike momentum. Maybe it’s just harder to operate a goliathan corporation with supply-chain issues hampering production. Perhaps it’s the increasingly fragmented marketplace dictated by TikTok algorithms over brand loyalty. At some point I stopped wearing Nikes as much and if I pause to think about why, I think it’s because I’m losing a personal connection with the brand.

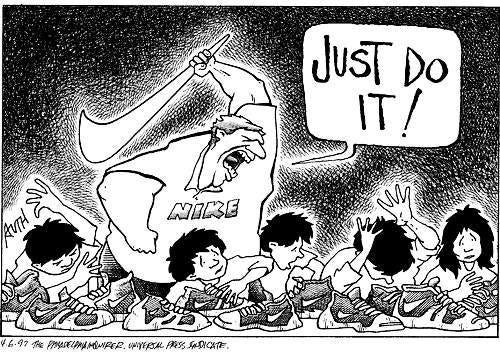

When I was a teen in the ‘90s, it wasn’t cool to wear Nike because of child labor cases in their overseas factories and accusations of slavery and human trafficking. Nike was a faceless and cruel corporation, a sharp contrast to the artist-owned skate shoe brands of the time like DVS and DC. Those brands felt familiar. When I pictured them, I thought of Tim Gavin, Ken Block, and Damon Way, not a concrete monolith in a necktie. Nike was discerning enough to recognize the value of credibility and authenticity in skate culture. When they launched Nike SB, they framed the marketing around legitimate sneaker collectors who just so happened to be some of the most iconic skaters in the world. Suddenly, Nike had a recognizable and friendly face and earned its way into subculture.

I’m assuming others have also been feeling the disconnect with the Swoosh in recent years. Although Nike stocks have been surging, the brand is continuously losing shelf space to New Balance, Asics, On, Salomon, and especially Skechers (!). The greatest contributor to Nike’s shrinking presence in physical retail? Nike itself. Starting in the mid-2000s, Nike made a deliberate effort to lean into Tech (Fuelband, Nike+, self-lacing shoes, SNKRS, and even Drake’s LED jacket). That also meant capitalizing on DTC (direct to consumer) business and e-commerce.

In 2017, Nike introduced “Consumer Direct Offense” (a digitally led initiative to home in on consumers through apps, data, and other tech) in the middle of one of the corporation’s most troubling years. As part of this shift to focus on their own channels, they whittled their 30,000 retail wholesale accounts down to 40 strategic partners and reduced their staff by thousands. Yet, Consumer Direct Offense was deemed a profitable business decision, especially in the pandemic. After the world entered lockdown in 2020, Nike’s new President and CEO John Donahoe re-interpreted Consumer Direct Offense as Consumer Direct Acceleration. Digital sales jumped 82%. At the time, CFO Matt Friend said, “Nike typically earns roughly 10 more points toward its gross margins on digital revenue versus wholesale revenue.”

John Donahoe’s appointment was symbolic. The former eBay CEO had an extensive Silicon Valley background, and he made it clear that his goal was to take Nike more digital. Nike, a global brand that is synonymous with peak performance was rapidly evolving into a supercharged, Olympian-athlete version of itself as a tech company. At $50 billion in revenue, Nike doubled adidas’ numbers in 2022 (to put things in perspective, a brand as successful as Supreme was projected to do about $500 million in 2022). Nike’s year-to-year business was up by 6% in a season when many major companies suffered losses.

The tech-forward decision to move sales through Nike’s direct channels was motivated by control, cutting out the middleman (retailers, distributors), and protecting the brand’s integrity. By not having Nike product associated with competitors on store shelves, they were reinforcing their own identity (they were also not helping anyone else out). Nevertheless, Nike was lauded for their ability to control their own merchandising and distribution channels.

By the end of last year, however, plagued by ongoing supply-chain issues, Nike was stuck with a glut of inventory. Leaning on retail partners played an effective part of the solution in clearing out product. On a December earnings call, John Donahoe clarified that accounts like Foot Locker were “very, very important” to Nike as wholesale rocketed 19% (this actually outpaced direct sales, which rose by 15%). In fact, Nike’s shared a symbiotic relationship with Foot Locker for generations. They even survived a $400 million pissing contest in 2003 to see who needed the other more to survive. The result was the acquiescence that they both benefited from one another.

The last couple years, as I wander deeper in Web3 work, it still strikes me how far apart tech and culture still are. Maybe it’s the dark side of technology portrayed in pop culture or the fallout around social media, but tech continues to carry a stigma of being cold, robotic, and impersonal. Targeted ads and data mining have transformed consumers into the product. Meanwhile, automation and AI threaten to absorb people’s jobs and purpose.

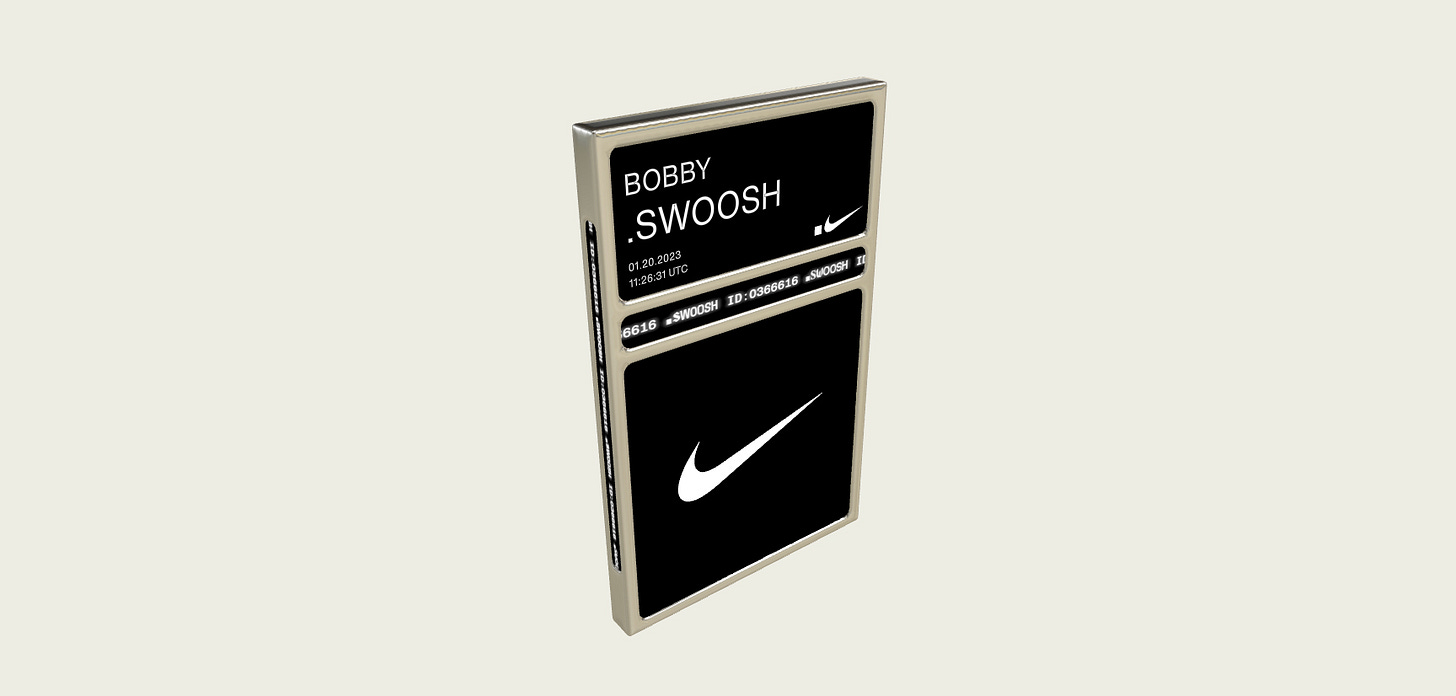

Having said that, I think any tech that helps people to clearly see and connect with each other is useful. The best technology is one that can amplify our humanness. Currently, Nike’s most impressive and promising digital endeavor is their Web3 platform, .SWOOSH. Without mention of the word “NFT,” members can collect and co-create digital sneakers, which then have the chance to be physically produced. Plus, designers will be paid royalties for their contributions. There’s one side of Nike playing out in the press as a bloodthirsty IP attorney (today, it’s Nike v. Lululemon). On the flipside is .SWOOSH, an effort to honor the Nike creative community and invest back into the culture.

For years, Nike had a bold and prismatic face in Virgil Abloh. The sneakers of this era resounded not just for their ingenious design, but Virgil’s ability to hold and reflect the people. The beauty was in witnessing Nike, one of the biggest corporations in the world, personified and made relatable via a single creative individual. In the future, .SWOOSH could multiply that success by empowering us all to become Virgils ourselves. “You can do it too.”

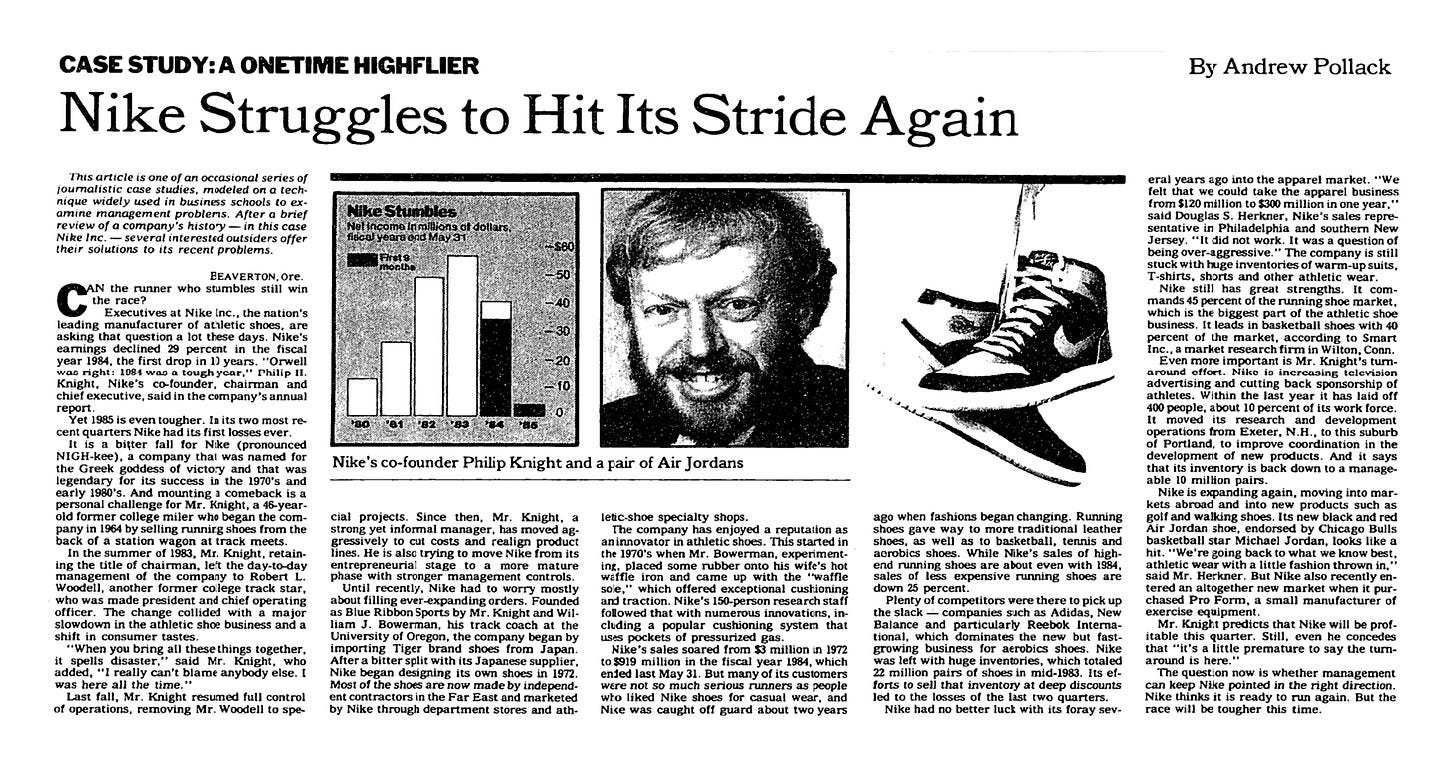

In 1985, Nike was enduring another tumultuous year. The company’s earnings plummeted 29%. In fact, it was the first decline in a decade. As today, Nike was saddled with too much inventory in the face of changing fashion trends and the rise of competitors like Reebok. Back then, Nike was a primarily a running-shoe company and the New York Times wrote, “Nike thinks it is ready to run again. But the race will be tougher this time.” Co-founder Phil Knight’s plan was to ramp up advertising and transition to different product.

One of those bets was on a 6'6" basketball guard from North Carolina. Michael Jordan was the 3rd overall pick in the ’84 NBA draft and an adidas loyalist who, as it turns out, wasn’t tall enough to be recruited by the three stripes. So, he signed with the Swoosh instead. In the months after A ONETIME HIGHFLIER; NIKE STRUGGLES TO HIT ITS STRIDE AGAIN, Michael Jordan’s first Nike shoe - the Air Jordan - would smash records by making $126 million in one year (this was even more incredible concerning Nike had expected to only make $3 million in the first three years).

Michael Jordan became the face of Nike. By the 1990s, the star athlete was one of the most famous people in the world next to the Pope and Princess Diana. Simultaneously, Nike catapulted from being a track shoe brand to the biggest apparel company on the planet. The relationship with Jordan was so fruitful for Nike that they eventually collaborated on their own standalone brand together called Jordan Brand (Yesterday, it was reported that in the past five years, Jordan Brand has made Nike $19 billion).

In Jordan’s fifteen seasons in the NBA, he also became the human embodiment of other businesses like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, and Wheaties. In August of 1992, Jordan starred in a Gatorade commercial in which diverse American children emulate his moves on the playground. A chorus sings:

Sometimes I dream

That he is me

You've got to see that's how I dream to be

I dream I move, I dream I groove

Like Mike

If I could be like Mike

“Be Like Mike” became one of the most iconic advertisements in TV history by snapshotting a generation of youth who identified with brands because they saw themselves in a person.

That same week, a workers’ rights advocate named Jeff Ballinger would write an expose on Nike in Harper’s, calling the company out for unethical business practices and child labor in Cambodia and Pakistan. Nike would spend the next several years rehabilitating its reputation (in fact, many modern slavery laws have been informed by Nike’s advancements during this decade) and reviving its sales. But in that moment, Jordan sneakers continued to fly and fans around the world wanted to be like Mike. Although the amazing part was that they really wanted to be like Nike.