On the weekend of August 19th, 2023, a Category 4 hurricane unleashed biblical floods and triggered earthquakes across Southern California. From San Diego to Santa Barbara, survivors sought refuge in the apocalyptic blackout. They lit candles, filled bathtubs and stockpiled gasoline as they waited weeks for the waters to subside.

Of course, this isn’t exactly how Hurricane Hilary played out. Although the storm did take one life in Mexico, felled trees, and caused mudslides, there were no reports of deaths or severe damage in California. There was record-breaking rain for the summer, however: about 3 inches worth (Enough that California is now drought free for the first time in ten years). Melrose Ave. got deluged, but this wasn’t anything new for an LA rainstorm. The fire dept. unplugged a manhole and resolved the issue. While experts and the media continued to warn LA and Orange County residents that the worst of the storm would batter their rooftops by late Sunday night, that threat never fully delivered. I can’t find stats to measure this storm against 2023’s other downpours, but this past winter, we had days where it hailed -- and even snowed! There were tornadoes outside of downtown! Yet, everybody went about their business as usual. So, what happened here?

At the start, the local government and media stayed relatively reasonable in sharing updates with the public. This time last week, there really was an unprecedented hurricane moving up through Mexico. If it stayed on course and maintained its strength, there was a potential for destructive winds and rainfall in majorly populated areas. But experts agreed that the hurricane would downgrade to a tropical storm over land. And although there would be heavy precipitation, very few people would have to evacuate or resort to extreme safety measures.

Yet, it seemed like the public seized the cautionary headlines and exploded them. By Friday afternoon, LA supermarkets were teeming with anxious shoppers, sweeping shelves for canned goods like it was March 2020 all over again. Neighbors shored up their yards with sandbags. One of the strangest turns was when both public and private schools cancelled class on Monday, what turned out to be the most beautiful day of the year with balmy 80-degree temperatures and clear blue skies. Even my kid’s basketball practice was cancelled Monday afternoon, although they hold it in an indoor gym. My work takes me all around Los Angeles. From the westside to the eastside to South LA, the worst of the flooding I saw by late Monday was a clogged drain by the corner of a Burger King parking lot.

I’m not much of a conspiracy theorist – not a very good one, anyway. Although the media does profit off sensational headlines and fearmongering, I don’t believe there are shadowy figures to blame for the overblown hype around Hurricane Hilary. No dark money changing hands to imprison Californians in paranoia. I’m sure what transpired this past weekend was more of a kneejerk reaction to the Maui brushfires. Out in Hawaii, authorities did such a lousy job of preparing their community for last week’s disaster, they were flogged mercilessly by social media. As a result, Californian officials most likely erred on the side of over-preparedness to cover their bases.

The trickle-down effect was that school districts, businesses, and churches also urged people to stay off the streets out of an abundance of caution, even though the threat had dissipated. Stores closed early this weekend, DoorDash paused orders for 24 hours, because: “What if?” It wasn’t even a matter of legal liability or being held criminally accountable in case things went awry. Social pressure, groupthink, and the viral judgment of Insta-shame and TikTok cancellation started to dictate emergency decision-making. Sunday morning, a meme circulated of Kim Kardashian in bed, studying her phone: “People in LA googling if they can still go to brunch during a hurricane.” Angelenos knew there wasn’t a hurricane, but they kept referring to it as such. It wasn’t even scheduled to rain for hours. They believed that they were safe enough to drive to Republique for mimosas. They just didn’t want to be judged for it by their peers and followers.

We hosted our annual in-person warehouse sale this weekend. In the days leading up to the event, we got chastised for putting our customers at jeopardy during a “hurricane.” “Crazy we in the mist (sic) of possible 65 mph winds yall trying to sell clothes.” That comment on our Instagram accrued 23 Likes with a series of supporting replies. What was fascinating was, at the time, every media outlet was reporting that the storm was set to begin AFTER our weekend sale had finished. In fact, Saturday was forecast to be sunny with clear skies. But it didn’t matter – people were expecting, and anticipating, the worst-case scenario (We postponed Sunday’s sale to next weekend).

There is a mental health condition called Catastrophizing. It’s when you anticipate and obsess over the worst possible outcomes, whether they manifest or not. You even psychologically prepare for and physically experience what it’s like to live through this imagined situation. There are many reasons as to why we catastrophize, from anxiety and depression to childhood trauma to simply the way our brains are wired. I know this because catastrophizing is familiar territory for me. When I was a teenager, a brushfire crept down the dry hills behind my house and I gathered our family’s photo albums and heirlooms into boxes to evacuate. My brothers laughed at me and continued watching Darkwing Duck. My mom didn’t look up from rinsing bean sprouts at the sink. No matter how much I pleaded with them to take the fire seriously, they thought I was overreacting or catastrophizing. The blaze was still at least a mile away and surely firemen would extinguish it before it reached the property line. The flames burnt themselves out by dusk.1

Lately, it’s felt like we’ve become very comfortable with a culture of catastrophizing. Or maybe we’re conditioned to it. When I pontificated about this on Threads, a follower answered, “a lot of us probably are on information burnout” while another remarked, “We’re all tired of the constant barrage of doomsday headlines.” It’s gotten to the point where we’ve gotten so used to alarm bells, that we expect them, maybe even count on them. If they don’t sound, then we raise the ladle to the pot and bang it ourselves. This is the dangerous endgame of catastrophizing – negative spirals often manifest unfavorable fallout.

Imagine you’re on a hike and a mountain lion emerges from a bush. At the next turn, there’s a cougar hiding behind a tumbleweed. Now, if you come across a hedge, you may panic. Especially if you see what appears to be a tail sticking out. But maybe it’s a twig. Maybe it is attached to an animal, but it’s a harmless squirrel. Catastrophizing would assume that every bush hides a savage beast, which would make it pretty traumatic to ever take a stroll again. You end up creating a negative experience where one doesn’t exist.

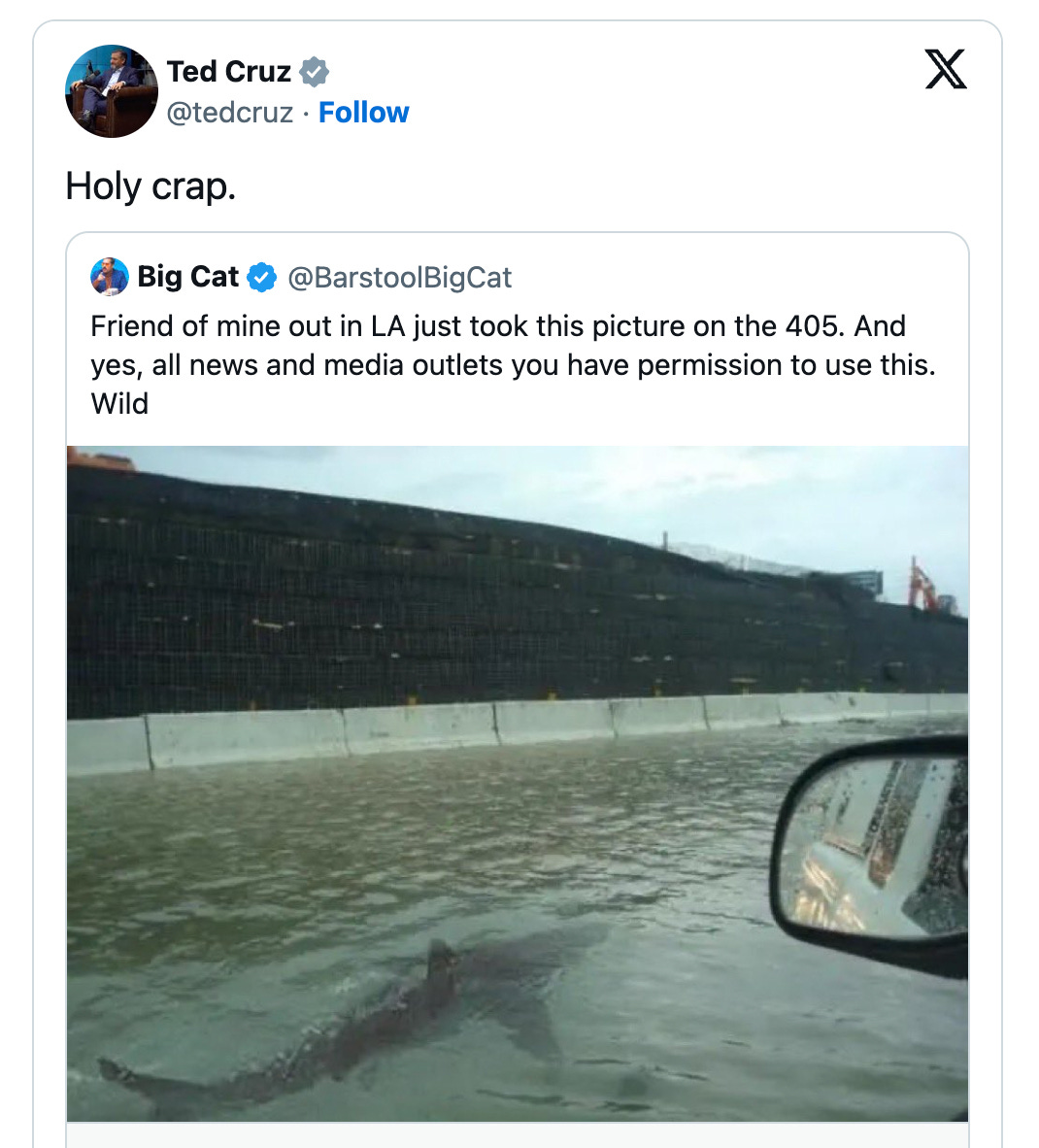

Hurricane Hilary was fertile ground for catastrophizing. It wasn’t just the troll on our page who believed cyclones would barrel down out of the heavens on a bluebird day, snatching up our warehouse sale shoppers like UFO abductions. Some of the most viral captures from the storm turned out to be fake or sourced from past events and yet the Internet gobbled them up. Senator Ted Cruz was startled by the sight of a shark on the 405 freeway, exclaiming, “Holy crap” to his six million followers. If it wasn’t obvious enough, the meme was photoshopped. In fact, it’s been making the rounds since 2015, but Cruz didn’t care. He left it up anyway. Ben sent me a trending TikTok of a flooded neighborhood that had gone viral. Meanwhile, the user had cleverly employed the flood filter on their driveway. And the Internet was aghast at the sight of a flooded Dodger Stadium. Prominent figures, some very smart and powerful, were quick to repost to their audiences. It validated their hurricane fears and confirmed everything they’d worried about. The next morning, this image was debunked as an optical illusion. And yet, like Ted Cruz, people continued to pass the misleading snapshot around as truth.

What has emerged are two experiences of Hurricane Hilary. There’s the scary one that people have constructed to feel like the first paragraph of my essay. And then there’s reality, which more closely follows the second paragraph. Considering how much of our memories and learnings are grounded in the Internet – and how much AI will write our future based on the way data aggregates online – it concerns me that we are intentionally, consciously, and knowingly narrating lies to ourselves. We are composing self-fulfilling prophecies that are fueled by fear, negativity, and anxiety, because we’ve become so accustomed to being dealt bad news. And we’re setting up a world where we imagine sharks on freeways and baseball stadiums in lakes so that we can feel justified when we publish it as true. It’s a stupid, ridiculous existence in which facts and truths continue to be distorted and perverted. And it makes for a mushier reality where bushes are life threatening and branches are ferocious tigers.

Or am I just catastrophizing?

Catastrophizing has played an integral part in my life and career. In fact, the flipside of catastrophizing is being sensitive to frontline trends and culture. It’s really about prediction and prescience. The problem with catastrophizing, however, is that you look hysterical for worrying about the fire. But if it comes, the vindication is late and bittersweet! See: Cassandra Complex

Years ago, we were under a tsunami watch and I was able to convince my family to evacuate to a friends house on the mountain. The tsunami never came but the same feelings of fear have stayed with me into adulthood. We had another fire break out in Kaanapali today. Thankfully, the sirens sounded and people evacuated but I believe our community is now largely steeped in catastrophizing. It’s hard not to feel that way after what happened in Lāhainā but I wonder how this will affect us in the years to come.

My mind is just tired ….