The Case for Nike

It's passé to talk about Nike's downfall. The more interesting conversation is how Nike comes back.

At $50 billion, Nike is the most valuable apparel brand in the world. But these days, the hottest Nike trend isn’t a retro basketball sneaker, celebrity partnership, or fashion collaboration. It’s dunking on the sportswear giant’s poor performance in the marketplace.

Editorial after the next has indulged in this dramatic turn of events. How Nike Ran Off Course. Is Nike Still Cool? The Downfall of Nike. In January, Tiger Woods left the Swoosh after 28 years and then Nike laid off 1,500 employees. In the Spring, Nike sales dipped for the first time in seven quarters. Nike had its worst day of its 53-year-old business in June as a stock implosion wiped out $28 billion from its market capitalization. Recently, another round of layoffs decimated the staff, with roughly 40% of top positions cut.

The TikToks, the barbershop banter, the Comments, all point to the same culprits:

CEO John Donahoe’s grave mistake in clipping wholesale partners to bet it all on Nike’s digital and direct channels.

A lack of innovation. Nike relies on the same 40-year-old Dunks, Jordans, and AF1s.

Failure to capitalize on the run club craze.

Most of the claims are valid. In the years leading up to the pandemic, Nike was on a tear. In 2016, Nike was selling 26 pairs of shoes a second and 96% of the sneakers on the resale market donned the Swoosh. When John Donahoe was hired as CEO in 2020, the former eBay chief executive officer introduced a bold plan to juice e-commerce and its 1,000 retail locations. Donahoe withdrew the brand from department stores and mall chains, angling for "a more premium shopping experience.”

Nike reported record results two years later post-lockdown, with mobile app revenue up 50%. But by 2023, consumers returned outdoors and the economy shifted. The sneaker resale market peaked and there was consumer fatigue. As demand and supply were evening out, Nike had no choice but to reverse course, backpedaling into big box doors like Foot Locker and Designer Shoe Warehouse. The line has plunged since.

Rarely mentioned are a gallery of other factors that have contributed to Nike’s misfortune. For one, sportswear has been slowing down across the board. Inflation is still high, throttling the retail economy. Meanwhile, fashion has its cycles. Shoppers are wearing big pants again, which obscure footwear and diminish their signal. I foresee vulcanized and cupsoles footwear brands (like VANS) having a revival to better complement baggy jeans and camouflage shorts.

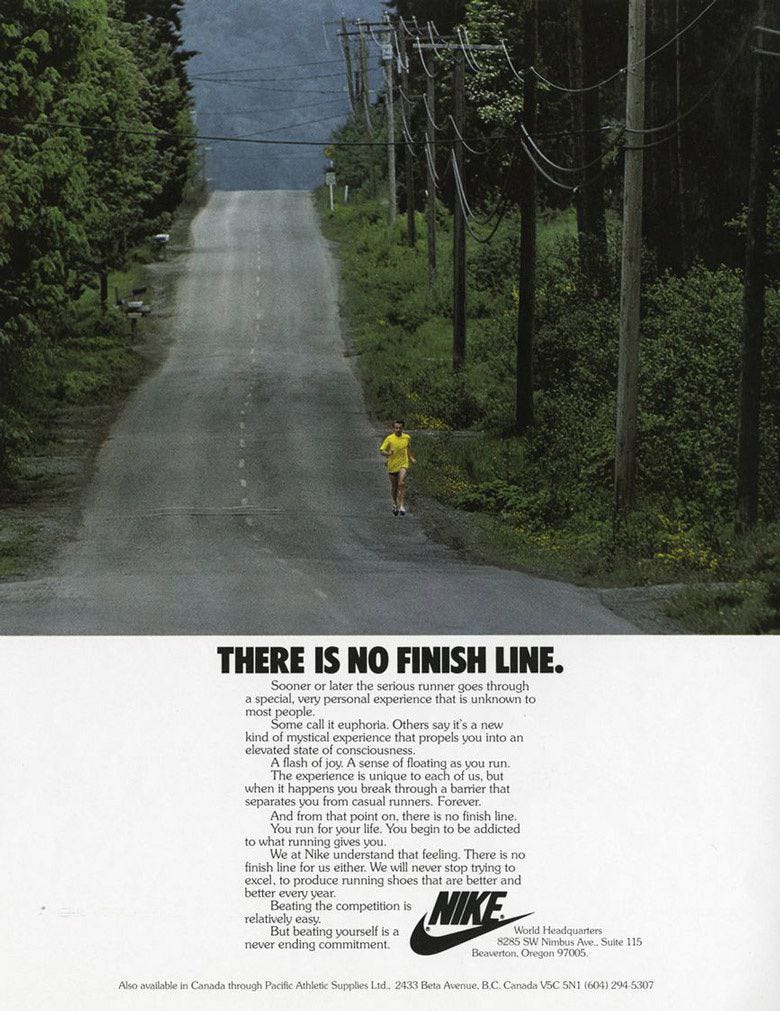

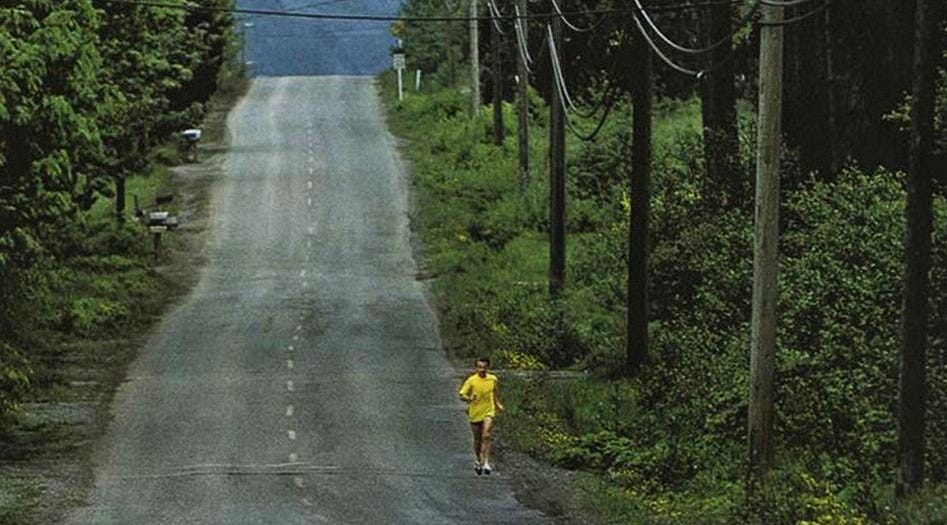

In 1977, Nike ran a seminal advertisement (by the late John Brown) that declared, “THERE IS NO FINISH LINE.”1 The featured subject is hard to make out -- a lone runner on an empty road. Nike historian Scott R. notes, “In the photograph, there is no discernible Nike Swoosh...the runner is so far away you can barely see him. [Photographer Bob Peterson] told me the goal was to "focus on the environment and not the runner."

Nike’s problems are existential to product and distribution. Much of their challenges are impeding other sectors like Tech and Hollywood. Zooming out, there are macro trends at play across culture, business, and human psychology that are having a larger impact on how a consumer considers a Nike shoe. Let’s take a second to focus on the environment.

THE PROBLEM

The End of Monoculture

This summer, my sister-in-law was visiting from Minnesota. She was wearing On, a 14-year-old Swiss shoemaker that has quietly risen in popularity. You’re probably aware of On by now, especially if you fly a lot. Like many sneakerheads, I scan up and down the aisles whenever I’m seated on a plane. The rows are lined with On’s proprietary CloudTec soles.

Over the last several years, On went from being a basic shoe for the undiscerning consumer (I used to lump them with tech-bro outfitters like Allbirds) to a relevant sneaker. Their campaigns are fronted by Zendaya, their Loewe collabs trade for $600 on StockX, and they even signed tennis great Roger Federer (who left Nike in 2018). But when I asked my sister-in-law why – and how – she was wearing On, she replied, “I had to return my Nikes because they were uncomfortable. Then, I went to Nordstrom Rack and tried these on. They feel amazing! Why? What is this brand?”

Quality issues aside, when Nike ditched 50% of its retail partners like Big 5, Dillard’s, and Zappos, they left a vacuum for new players like On and Hoka to infiltrate. Meanwhile, “dad shoe” underdogs like New Balance and Asics shot up in the ranks alongside rising interest in outdoor pastimes. Nike’s monopoly on the shoe wall shattered, and the consumer palate diversified. Footwear fans aren’t just renouncing marquis brands, they’re rethinking the convention of shoes altogether. Crocs, mules, and MSCHF Astro Boy boots have played with the sneaker’s classical form and function. They’ve topped end-of-year lists as a result (this year, it’s all about Clarks and Timberlands).

“Maybe it’s not that we have less monoculture today; it’s that we’re more aware of everything else in the other quadrants of the chart.”2

We don’t sit around the water cooler discussing the same TV shows anymore. So, it makes sense we aren’t faithful to one footwear brand. Decades ago, David Muggleton was already observing that consumers were becoming “sartorial bricoleurs,” writing, “Today there is no fashion, only fashions” (Inside Subculture). So sure, monocultures may be dying. But I’ve always found it strange that Nike prevailed with such domination in the first place.3

Americans v. Big Business

In 2008, writer Rob Walker interviewed Yu-Ming Wu of Freshnessmag for his book, Buying In. Rob assumed, “Given all I’d heard about the new generation of young consumers shunning mainstream brands, that I’d find plenty of skepticism about a megabrand like Nike in the brand underground.” He was surprised to learn that sneakerheads like Wu worshipped Nike with statements like, “Instead of stealing ideas from the underground, the big sneaker makers positioned themselves as supporting it.”

I was also a Nike dissident-turned-loyalist at the turn of the millennium. As a teen, I decried the corporation for co-opting authentic culture. Then, I became obsessed with sneaker collecting because of Japan’s otaku spin on rare vintage. I spent years hunting for obscure colorways of adidas and Puma from Harajuku to ALIFE and KBOND. But today, American shoppers hold a strained relationship with big business, influenced by sentiments around wealth disparity and corporate abuse (From Occupy to Big Tech and Big Pharma). In the presidential race, both candidates use small business as a talking point to win the sympathy of voters. As trust in institutions (church, banks, colleges) sinks to all-time-lows, faith in small business is up, transcending political lines, with “nearly all adults (97%) [having] a positive view of "small business."

For years, the easiest way to see consumer disdain for Nike’s cold corporate persona was by reading the comments under SNKRS releases. Nike’s app was responsible for exclusive shoe drops, but only “7% of shoppers” were lucky enough to purchase the product as the company couldn’t keep up with the demand. Although the sneaker community blamed resellers and bots for tarnishing the experience, many pointed the finger at Nike for scamming them. One sneakerhead tweeted, "I'd rather camp out for 15 hours and get robbed as soon as I get out the mall than to open SNKRS app ever again."

I was talking to my friend Jeff Malabanan at the sneaker store RIF who also took issue with Nike’s corporate greed. “It was big moves these brands made that just left a bad taste in their mouth… Nike is literally committing suicide bringing back the unicorn sneakers. Some things are just better left untouchable. That's what kept Nike special. A lot of Nike friends agree, but they said the leaders made the ultimate decision.”

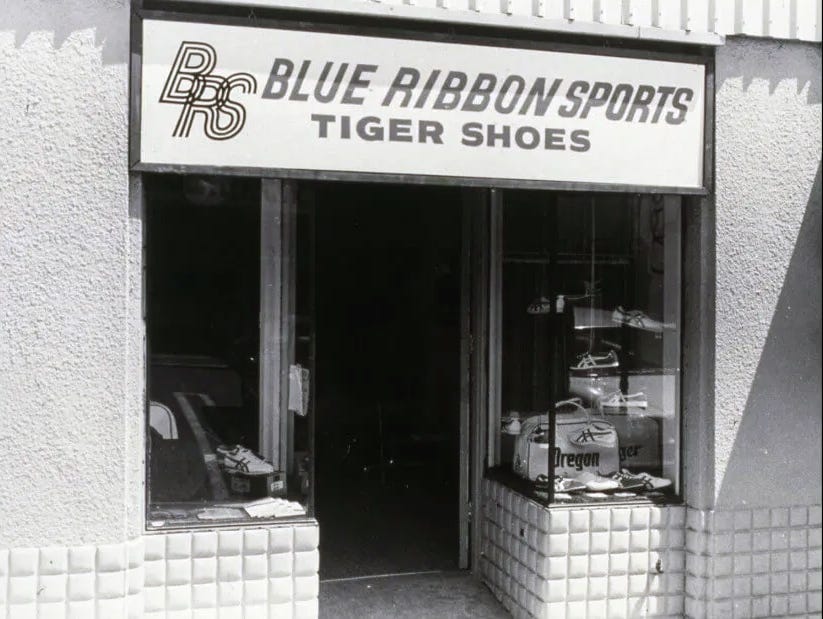

Even Nike’s co-founder and chairman, Phil Knight, was once opposed to big business. In fact, Nike was forged as a small business in the early ‘70s when Knight chose to break Blue Ribbon Sports (Nike’s original brand) away from Japanese parent company Onitsuka.4

The Death of Brand

Maybe it’s not about big or small. Maybe it’s about the death of Brand as a whole. I wrote exhaustively about this trend in my last Substack, but it’s worth applying to Nike here. To reiterate, today, it’s all about targeting the consumer with product, not the lifestyle or culture of a brand. Marketing guru Scott Galloway uses Apple as an example. The tech giant once relied on “brand-based advertising.” Today, its ads are nearly “all product-based.”

This would explain my sister-in-law’s decision at Nordstrom Rack. She wasn’t persuaded by brand name in buying a new pair of shoes. She was driven by accessibility, quality, and comfort. American shoppers are also motivated by price and value these days. Gen Z relishes in reps, dupes, and cheap SHEIN hauls. These are the same kids that would have been wooed by bright red Supreme box logos just a decade ago.

THE SOLUTION

The ‘80s died on April 2, 1993. Coined “Marlboro Friday,” the leading cigarette brand announced that it was slashing prices by 20% to compete with the influx of generic brands flooding the market. This signaled an end to a decade marked by big brand aura c/o global banners like Pepsi, MTV, and Levi’s. In her scathing indictment of capitalism, No Logo, Naomi Klein writes, “bargain conscious shoppers, hit hard by the recession, were starting to pay more attention to price than to the prestige bestowed on their products by the yuppie ad campaigns of the 1980s…The public was suffering from a bad case of what is known in the industry as ‘brand blindness.’” Pundits agreed that this was the Death of Brand as we knew it.

Four decades later, we’re once again questioning the purpose and impact of Brand. And we are right back to doubts about Nike’s future, engaging in the same discussion that may sound hauntingly familiar.

For the better part of the 1990s, Nike was out in swaths of youth culture. Grunge didn’t take likely to the Swoosh. Neither did underground movements like skateboarding and Lilith Fair feminism. But most unfashionable of all, Nike was mired in social controversy. Cancel culture hit differently back then. Actors like Pee-Wee Herman and Hugh Grant got sidelined for decades. Tommy Hilfiger still carries a scent of racism accusations, no matter how many times they’ve been debunked. And Nike, coming off a roaring ‘80s where they were bigger than Michael Jackson, was sacked with sweatshop labor allegations.

Phil Knight finally addressed these claims head-on in a 1998 press conference. Confronting smears that “Nike represents not only everything that’s wrong with sports, but everything that’s wrong with the world,” he also answered investment bankers who heckled, “Nike isn’t cool anymore.” Nike’s sales were suffering from an Asian market meltdown. Knight also mentioned consumer trends rerouting from “white shoes” (tennis, basketball) to “brown shoes” (trail).

Like sneakers, everything old is new again. A quarter of a century later, Nike once again blames China’s slowing growth for its downturn, as well as hiking shoes like Salomon and Merrell swallowing up market share. After the press conference, Nike surged in sales in the 2000s, so what can we learn about how they overcame these troubles the first time?

First, Nike knew it was futile to engineer brand relevance, while product relevance was paramount. Knight stated, “If we’re gonna be successful again, we don’t try to be cool. You can’t manage Cool.” However, “We try to be innovative maker of shoes and clothes and great product and advertising that go with it.”

Marketing

Nike’s prowess is not in selling shoes and apparel, but in the dream around them. In 1981’s The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self, the authors discovered that “People do not buy objects, they buy ideas about products.” In No Logo, Klein comments on, “the now ubiquitous Nike model: close your factories, produce your products through an intricate web of contractors and subcontractors and pour your resources into the design and marketing required to fully project your big idea…What these companies produced primarily were not things, they said, but images of their brands. Their real work lay not in manufacturing but in marketing.”

In 1987, Nike sales had dropped by almost $200 Million and the brand hemorrhaged 280 employees. Although we have a rose-colored impression of the ‘80s as Nike’s golden age, they had bet on the wrong horse, concentrating on running while the mainstream was infatuated with aerobics. This was Nike’s first true test, but instead of caving, Knight doubled down on advertising. “Nike pumped an extra 24.6% into its already soaring ad budget, bringing the company’s total spending on marketing to a staggering $250 Million annually...[Nike] emerged from the recession with profits 900% higher than when it began.”5

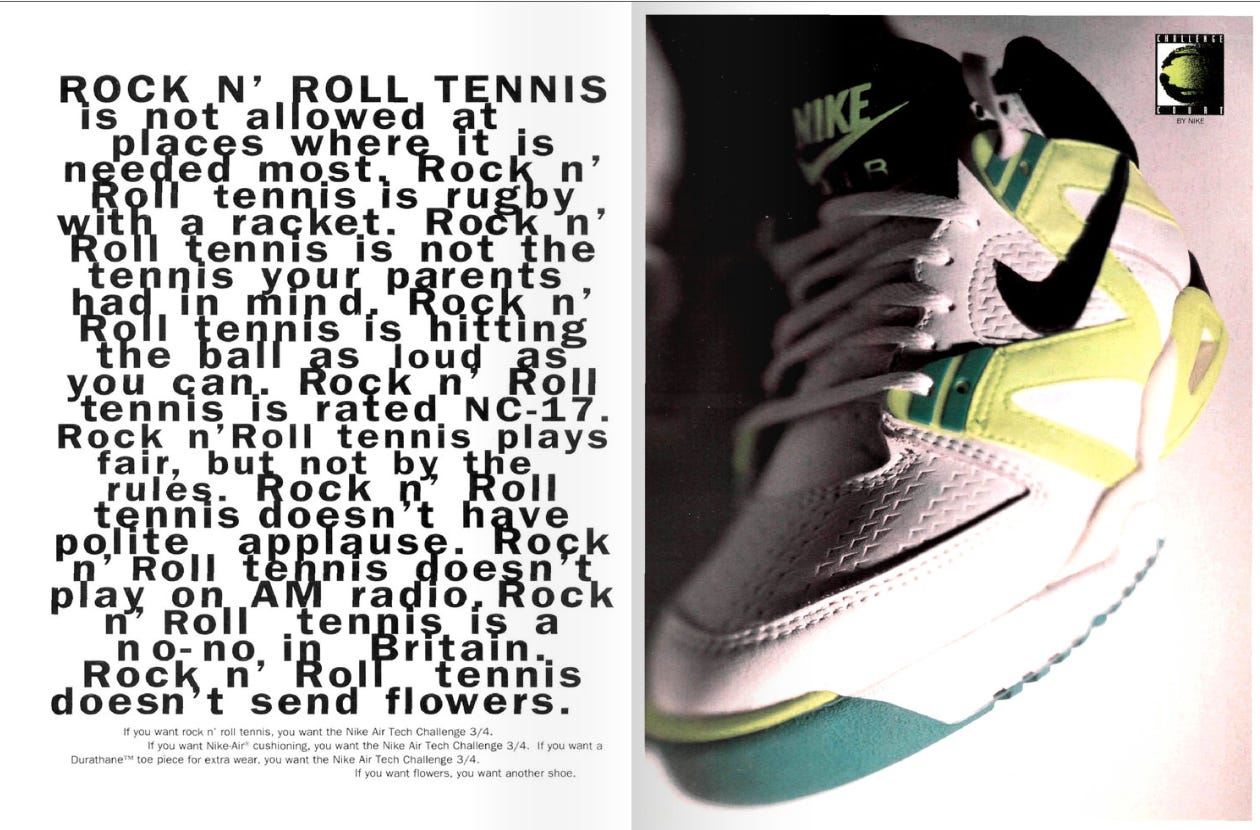

In the ensuing years, you may remember this series of ads:

1988: “Just Do It”

1988: Spike Lee as “Mars Blackmon”

1989: Bo Jackson in “Bo Knows”

The Air Jordan campaign, as well as Air Max.

Product

But you can’t have a memorable movie without a great protagonist. According to Knight in a 1992 Harvard Business Review interview, “you have to start with a good product. You can’t create an emotional tie to a bad product because it’s not honest. It doesn’t have any meaning, and people will find that out eventually. You have to convey what the company is really all about, what it is that Nike is really trying to do.” By the late ‘80s, Knight new Nike had to deliver on a fresh idea. And it wasn’t aerobics (Thank God). Enter Air Jordan and Nike’s basketball shoe reign:

“The Air Jordan project was the result of a concerted effort to shake things up. With sales stagnating, we knew we had to do more than produce another great Nike running shoe. So, we created a whole new segment within Nike focused on basketball, and we borrowed the air-cushion technology we had used in running shoes to make an air-cushioned basketball shoe.”

Years earlier, Forbes had written this about Knight’s strategy with product, even in its earliest iteration. “Knight is no amateur. He recognizes that fashion’s fervor will cool if you don’t keep a fire under it. As soon as one of Nike’s 140 basic models shows signs of petering out, Knight replaces it.” At the same time that Nike was ramping up its basketball division (Flights, Dunks, Terminators), it reinvented their bread-and-butter -- running shoes -- with the Tinker Hatfield-designed Air Max and the first visible air bubble. The program was kicked off by the commercial, aptly titled, “Revolution.”

Which, makes it all the more curious that Nike is now being flamed for rehashing the same designs.6 Phil Knight once said, “If you do the same thing you’ve done before or that somebody else is doing, you won’t last more than one or two seasons.” So why, then, has Nike drowned the marketplace with Jordans and restocked the Panda Dunk to death? The answer may lie in more than sluggish business moves or greedy opportunism.

The Religion of Money

If Taylor Swift has eras, Nike does too. This is my subjective breakdown (Note how closely they align with America’s cultural history - symbiotic!).

The ‘70s were about philosophy and performance.

The ‘80s were about pop.

Nike in the 1990s was reckoning with its humanity.

The 2000s were about rebuilding.

The 2010s were about victory, as business and culture (art and commerce) coalesced.

The last several years, and certainly the 2020s, have been about money. In 2024, money is the biggest fashion trend of all (See Zuck).

This is not a judgment, nor is it a secret. You don’t become the biggest apparel brand in the world by not prioritizing money. The fact I’m writing this essay indicates how conflated the $woo$h has become with $$. What I’m talking about, however, is what happens to brands when money comprises everything. Or, put differently, if money becomes the only thing.

Nike is emblematic of society at large. A recent WSJ/NORC poll found that Americans are pulling back from traditional values like patriotism, religion, and hard work. Instead, “money” is skyrocketing as an “important” value. This is the natural consequence of a hypercapitalist society that makes celebrities of families for being rich and elected a President for his financial stature. But we’ve been heading in this direction for centuries.

Until the 1850s, Americans gauged each other’s value and credibility by moral statistics. “Their unit of measure was bodies and minds, never dollars and cents.” But then we started looking at everything around us as money-makers. “Basic elements of society and life—including natural resources, technological discoveries, works of art, urban spaces, educational institutions, human beings, and nations—are transformed (or “capitalized”) into income-generating assets.”7

Streetwear had a couple decades to establish itself as an artistic movement before it was bottled as a capitalized investment. Supreme’s later growth was spurred by profiteering resellers. In Buying In, Rob Walker identifies hypebeasts8 steeped in hustle culture as “A new layer of people – half consumer, half entrepreneur – who snapped up hot commodities with the sole intention of reselling at a profit.”9 Consequently, shoes have been reduced to a variable, holding the same meaning (or meaninglessness) as a stock or any other tradeable asset (Many sneakerheads have graduated to flipping stocks, trading crypto, and sports gambling).

For every Nike misstep over the generations, Phil Knight’s atoned by infusing the product with value – namely, ramping up quality and innovation. But what happens when consumer psychology shifts? What does Nike do if the shopper perceives value as prestige or profitability instead of performance? The game becomes less about technical design and superior construction and more about scarcity and clout. Critics say that above running and basketball, “making money” was the sport that Nike embraced for a new breed of competitor. And by relying on “data-driven insights rather than cultural and creative nous,” nobody played the game better than Nike.

Emotional Stories

In The Meaning of Things, people were asked, “What are the things in your home which are special to you?” As you probably guessed, they weren’t the priciest or flashiest. “The most meaningful objects were rarely chosen on the basis of some intrinsic, rational property, like marketplace value, cutting-edge quality, simple aesthetic pleasure, or anything that an economist might describe as ‘utility.’ They were chosen instead for connections to something else: family or social ties, a particular episode in the narrative of the subject’s life, perhaps religious faith or some other belief system affiliation.”

That book was published more than 40 years ago. Yet, I still believe the objects we cherish most are associated with memories over money. Black IVs, Air Tech Challenges, Forbes SB Dunks – these classic Nikes intersect with various stages of my life, from the schoolyard blacktop to summer camp to Niketalk.10 In the HBR interview, Phil Knight said, “From the beginning, we’ve tried to create an emotional tie with the consumer. Why do people get married—or do anything? Because of emotional ties. That’s what builds long-term relationships with the consumer, and that’s what our campaigns are about.”

As trust in institutions and goliath corporations erodes, it’s imperative that Nike restores that human bond with its community. I’m not just talking about IRL events, retail experiences, touching commercials, or microinfluencer UGC on social media (although these all help). According to Claremont University neuroscientist Paul Zak, “We need to develop an emotional connection to regain trust or form a trusting connection with a person or institution. We can do this by…telling emotional stories.”

Emotional storytelling softens the blunt corporate edges of big business. It elicits empathy from the consumer (think of the SNRKS app) and makes the brand relatable. But it goes even deeper than that. Good stories tell you something about the hero. Great stories tell you something about yourself. When emotional storytelling is done right, the consumer learns who they are. And they use parts and pieces of the brand to not only reflect their worldview, but to create their identity.

Back to Morrison, the sneakerhead who passed up on the LV shoes. “All are looking for sneakers that speak to the culture of their day…They’re more than just something that goes on your feet – they’re a canvas that serve as a means of self-expression, whether you’re a collector or wearing them right out of the box.” What is lost when sneakers are interchangeable with money is the opportunity for self-expression. The irony being that this is the foundation of Fashion.11 “It’s the ‘cultural construction of the embodied identity.’”12

The last time we were enraptured by an emotional story out of Nike was the late Virgil Abloh. The artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear collection got his start as a T-shirt designer and architecture student out of Chicago. His design identity was an assemblage of his high school years, “playing soccer, skateboarding and biking year-round.” Born to immigrant parents, Abloh collaborated early on with Kanye West. He then founded Off-White, which became the hottest brand in the world. In 2017, Nike invited Abloh to design “The Ten,” remodeling ten of their greatest hits, which then became the greatest hits for a new class of sneakerheads.

If Nike sport was personified by Michael Jordan, then Nike fashion was portrayed by Virgil Abloh. Virgil’s ascent was also happening during a time when young people were aspiring to enter the fashion industry, the way the 2000s broke open hip-hop music. Unlike Jordan, Virgil took his community along with him for the ride, being transparent about his process, and corresponding with most everyone who sought to interact with him. He became the face of a new Nike, an inspirational and inclusive Nike (and what would eventually be deemed as a woke Nike). Before he was interrupted in 2021, Virgil’s legacy had already been planted in an expansive culture of artists, musicians, and entrepreneurs whose identities had been built off his ideas.

THE REVOLUTION

“While once people thought a true painting or a poem or a protest march could revolutionize society, now you have people such as Nike’s Phil Knight who talk as if a sneaker can.”

When people talk about how Nike started, they tend to bring up co-founder Bill Bowerman’s waffle trainer story – how the University of Oregon running coach poured polyurethane into a waffle iron so that his runners’ shoes could grip the track without spikes. This lends to the narrative that innovation – from air bubbles to Nike+ to the SNKRS app – has catalyzed Nike’s breakthroughs along its way.

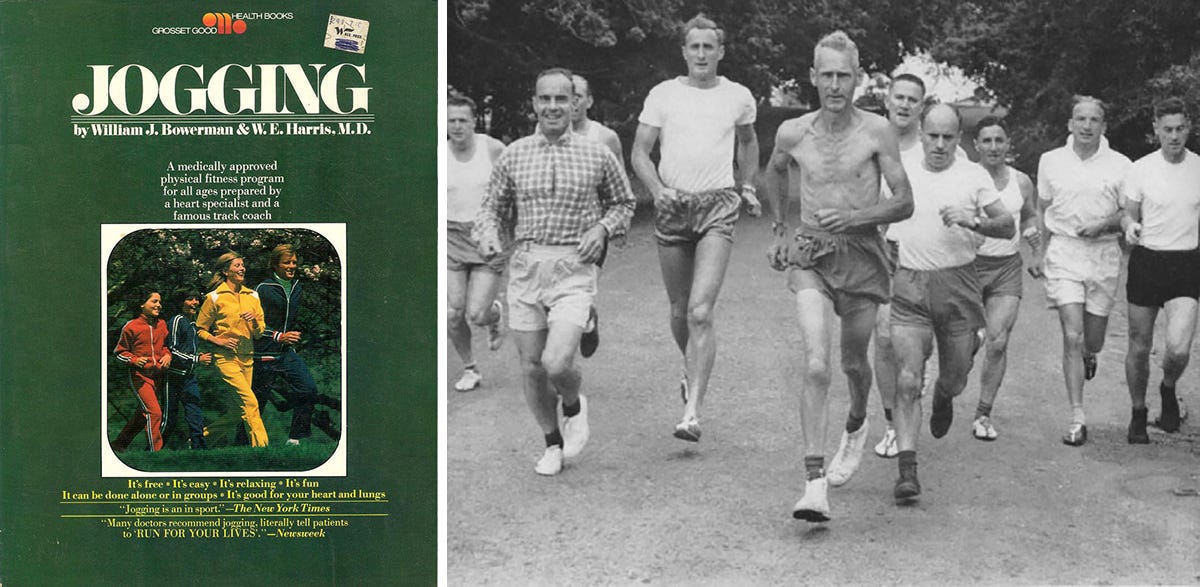

But talking about the technology without the philosophy is like talking about Mark Zuckerberg building Facebook without his lust for love and acceptance. My telling of the Nike origins story begins with Bill Bowerman’s book, Jogging. Published in 1966, the 90-page book was inspired by a trip to New Zealand, where Bowerman witnessed communities of ordinary people jogging. “The events that transpired demonstrated a recurrent, dominant theme in Bowerman’s work: applying the dictates of world-class competitors to the needs of everyday citizens.” The book became an international bestseller and Bowerman was known as the man who re-invented jogging. Shortly afterwards, Nike released their first shoes, and they exploded out the gate.

In today’s context, it may be hard to see how jogging was revolutionary, but what Bowerman was doing was designating a high standard and then demanding the best of everyday individuals. “Here’s how a world-class athlete trains. And here’s the book that will get you there.” Now, replace “book” with “shoe.” As an extraordinary coach does, Bowerman saw something more than money within the consumer. He saw excellence, greatness, and the ability to better one’s life. And he believed that his shoes could facilitate the trajectory (the way I believed that Jordans would help me jump higher). Now, that’s an emotional story.

There are a million paths forward for Nike and they will all lead to the same destination (although some may take longer than others). For one, Nike could retire the Swoosh or replace it with something new (This wouldn’t be the first time). Nike is so down bad right now, that the “check” carries a stigma that distracts from good design. I think the Vomero is Nike’s most attractive contemporary silhouette, but the better colorways keep the Swoosh tonal or monochromatic. A little distance from the Swoosh wouldn’t hurt.13

Maybe Nike could lean more intentionally into fashion while footwear heals (although this has gone awry in the past). Or maybe Nike can explore beyond fashion – AI, food and beverage, entertainment – as long as it aligns with the company’s narrative. Low-hanging fruit would be brand segmentation or investment into independent artists and brands. This way, Nike can stave off the “big business” connotations while diversifying its platforms. My generation of streetwear sprung from a cohort of street artists that Nike was forward enough to identify and tap into. “I still wonder who will be the next influential figure like Stash, Futura, Kaws, or Mister Cartoon,” says Jeff from RIF. Marvel has a universe of IP that’s been parlayed into consumer products, media, and theme parks. Nike could have one also. They can own podcast networks, win Emmys, and reimagine the Olympic Games.

The other thing I’ve been thinking about is the next era of Nike, which leads me to wonder about the human condition. Once we’re past the money, I think there will be a moment of clarity around hard work and earned wins. From the Tech boom to stimulus checks, money’s became so ubiquitous, that it’s lost some of its spirit. It’s almost shapeless and absurd at times, with Gen Z experiencing “money dysmorphia.”

Now that the economy has downshifted, it will be harder to make money, but it will be more meaningful to do so. This is a dog-eat-dog world, but the bone will be worth saving. Perhaps the material items we buy will be imbued with significance, then, as opposed to a placeholder for money. We will know we’re in the next era when we buy things to keep, rather than buy things to sell.

There is an “I” in NIKE.

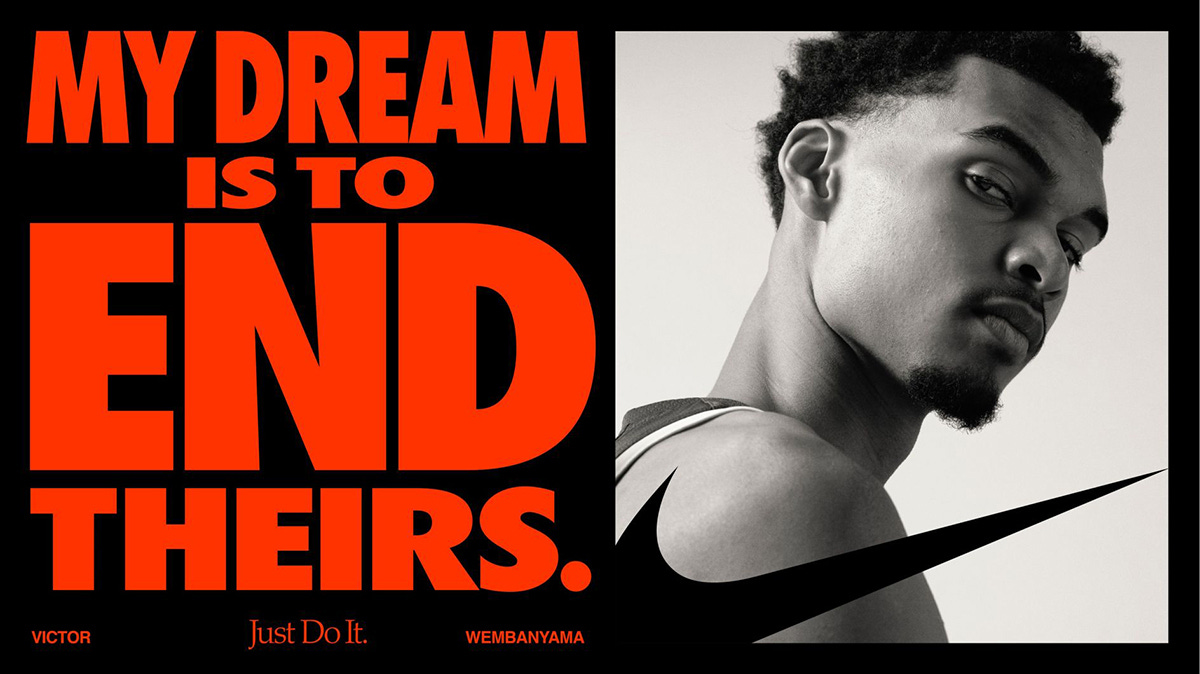

In tandem with the Summer Olympics in Paris, team sponsor Nike rolled out their latest campaign around a slew of new product offerings, amongst them the Alphafly3 and Pegasus. Entitled, “Winning isn’t for Everyone,” the series of commercials were montages of notable athletes and everyday folks playing sports. The first, “Am I a Bad Person?” features actor Willem Dafoe’s voiceover. Dafoe rhetorically questions whether he is of poor character for thinking he is better than everyone else. “I have an obsession with power,” Defoe sneers. “I have no sense of compassion.”

The advertising campaign stirred controversy for its sociopathic nature. Today’s consumer is accustomed to platitudes like “Winning isn’t Everything” not “Winning isn’t for Everyone.” The participation trophy generation believes that, like Virgil professed as he closed out his Louis Vuitton runway show, “You can do it too.” But Nike’s about-face suggests a hot take: Maybe you can’t. In fact, you probably won’t.

There can only be one winner, which means everyone else is a loser. This is an attitude that hearkens back to Nike’s inflammatory “You don’t win silver. You lose gold.” ads from the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Other taglines from the set: “If you're not here to win, you're a tourist" and "Pageantry is a distraction."

Although “Winning isn’t for Everyone” missed the mark with the public, it did register with one group: legitimate athletes. “The general population gave the ad a 1.5-star rating (one of Nike’s lowest scores ever), while sports fans who appreciate the competitive mindset gave it a more favourable 3.8 stars.” Although divisive, Advertising Week reported, “This was a deliberate repositioning campaign that clearly sought to reconnect Nike with its core athletic audience,” with some journalists noting an uptick in searches as a win for the brand.

Michael Jordan was Nike’s avatar for the better part of my youth. Arguably the greatest athlete of all time, Jordan was celebrated as a god. But hardly anyone would color his reputation as generous or benevolent. MJ isn’t answering fans’ questions in the DMs or putting on young artists who need a shot. Jordan was exclusive, not inclusive, and the Nike brand during that time channeled the ruthless winner’s mentality. It is probably timely then that Nike is investing so heavily back into Kobe Bryant. Ask any younger basketball player these days and they will tell you Kobes are the coveted shoe on the court. But the same judgments were also made about Kobe when he was alive. Kobe was hardworking. Relentless. Dedicated.

But, Kobe was arrogant. Selfish. Not a team player.

For decades, Nike has been a team player. The company worked tirelessly to repair their image after the sweatshop scandal. They used the crisis to reinvent the entire business14 and their “renewed focus on social responsibility [was] helpful in re-establishing Nike’s brand as a name embedded with a social purpose.” They are so honest now, that you can read more than 150 reports of Nike factory inspections conducted by independent third parties on the Fair Labor Association website. They’ve led the charge on social justice and embraced cultural inclusivity, stood up against anti-LGBTQ sentiments, and become a platform for the people. Winning may not be for everyone, but Nike is. Nike is not just running or basketball anymore. They are skateboarding and breakdancing and video games.

Contemporary streetwear owes much of its proliferation to Nike’s cooperative outlook. Nike has done a lot for the culture in terms of collaborations and recognizing smaller independents. In fact, it is because of them that so many of their footwear competitors get to play in the league. As talented and sophisticated as these rising stars are, in many regards, they are merely following Nike’s playbook, building atop their infrastructure. Limited-edition drops, gatekeepers curating tastemakers, cultural endorsements. Here’s the thing. In my opinion, Nike not only let them. Nike fostered this healthy competition. High five, TEAMWORK.

Whenever I read another online jab or thinkpiece about Nike’s decline, I imagine that, like Jordan, the higher-ups in Beaverton are muttering, “and I took that personally.” I also envision them opening the next era of Nike with a Jordan/Kobe attitude of Self over Community rather than Community over Self. I don’t think that means Nike will become callous (Remember, it will be fundamental to tell emotional stories). But I do think Nike will aim to win at all costs, employing ingenuity, sweat, and grit. The asterisk on that statement, however, is in asking, “Win against who?”

Although Nike’s sales are struggling, they are still in another stratosphere compared to the buzzier brands.15 Let’s put things in perspective. “Nike [generated] revenues of just over 29 billion U.S. dollars in 2022. This figure is larger than the combined footwear revenues of its two closest rivals, adidas and Puma.” Nike doesn’t just write the playbook. They choose the field. They pick the uniforms. And they write the rules.

A runner makes his way down the road, passing telephone poles against a lush, forested backdrop. You can almost hear the man huffing as he wipes his brow, the patter of his rubber soles as they hit the asphalt. The only other sound is of the trees applauding around him, the leaves clapping, cheering him on. There are no other runners in the THERE IS NO FINISH LINE ad.

In the New Year of 1963, when Bill Bowerman was invited to run with the Auckland Joggers Club in New Zealand, the only objective was to complete the jog, not to beat the others to the finish. As Bowerman found himself trailing to a 74-year-old man with no athletic history, he was motivated to get in better shape. He was in competition with himself. And since then, Nike has been playing against themselves. A game that they invented, mastered, and is theirs to lose.

There is no finish line.

The body of the ad copy closes with this:

“Beating the competition is relatively easy. But beating yourself is a never ending commitment.”

Some believe “THERE IS NO FINISH LINE” captures Nike’s ethos better than “JUST DO IT.”

Years ago, we introduced a footwear brand (The Hundreds FOOTWARE) guided by the specific hypothesis that not every cool kid wants to wear a swoosh, right? We were grossly mistaken. In some of the stores we sold to, Nikes were 99% of the offerings – and these were skate stores! When I was a teenager in the 1990s, Nike was a four-letter-word in the subcultures. Now, it didn’t matter if you were a dad, a fashion designer, an emerging artist, or a jock – you wore Nike.

In the year 2000, author and columnist David Brooks found the irony in this. “It’s the big mainstream business leaders that now scream revolution at the top of their lungs… It’s Nike that uses Beat writer William S. Burroughs and the Beatles song “Revolution” as corporate symbols” (The Beatles would later sue Nike for $15 Million for using their song without permission).

Klein, No Logo

“For Nike, that 2017 changed the direction of the company. They grew. Nike was opening stores, but they introduced a program called edit to amplify. Edit to amplify made Nike focus on the product that was selling the best. And in the process of focusing on the product that was selling the best - Air Jordan 1, Nike Dunk, Nike Blazer - they began to make those shoes in a lot of different colorways, but the problem was they were no longer innovating. Nike used to be revolutionary. In the last few years, though, it's just Dunks, Jordans, Air Force 1s.” https://www.npr.org/2023/06/02/1179850224/is-nike-past-its-peak-a-look-at-the-companys-current-slump

A popular trend in the 2010s was kids filming flexing videos where they boasted of the price tags on their clothing (as opposed to story, design, or meaning).

In 2021, CNN published an article about sneaker collecting as a multi-billion-dollar industry. They opened the piece with a collector, Derek Morrison, who harbored regrets of foregoing $1,000 Kanye West Louis Vuitton shoes. A decade later, they would’ve resold for 10x the price. Morrison wasn’t distraught because he lost out on a cool pair of shoes though. He was bummed that he missed out on an easy $9,000. This editorial was featured in CNN’s Style section, but it should have been in Business or Finance.

“That's where you learned that there were other weirdos like you in real life. People came to Niketalk for the sneaker information and stayed for the conversation. The General and Music forums were where sneakerheads were able to discuss their daily lives, interests, and connect with sneakerheads on things that weren't just sneakers.”https://www.complex.com/sneakers/a/tommie-battle/how-niketalk-changed-the-sneaker-game

In the fourteenth century, tailoring loose-fitting robes closer to the body amplified personality and human expression. In Dress Codes, Richard Thompson Ford remarks that this shift in consciousness inspired the “modern individual.” Fashion was the birth of Identity.

Fashion in the Face of Postmodernity, Charlotta Kratz and Bo Reimer

Once in a while, bands need to break up to give the fans a chance to miss them again. Years later, they make a comeback at a Coachella reunion and the band gets to reset the board.

Shoe Dog, p. 373

“Nike’s fourth-quarter earnings…showed a year-over-year revenue decrease of 1.7% for the quarter, to $12.61 billion. On and Hoka … do a small percentage of Nike’s sales, at about $2 billion each per year.” https://www.glossy.co/fashion/on-and-hoka-are-gaining-market-share-as-nike-reports-sales-declines/

This was an amazing article over all thank you. As someone that started with Nike in the spring of 89 what I remember hearing about overcoming Reebok in aerobics was number one Nike had a pipeline of the great leaders, number two they had finally found a way to make air visible to end number three was the strategy of we're losing the aerobics conversation let's change the argument and they invented cross training and then they put tons of advertising behind it with Bo Jackson.