There’s a thing us young-at-heart American folks do where we sit around and sentimentalize dead retail stores and defunct restaurant chains. I’m not exactly sure why we do this. I guess, before the Internet, nationwide retailers were a shared culture for the Pepsi generation. However, unlike timeless environments like the community pool or neighborhood basketball courts, many of our childhood memories are associated with brick-and-mortar brand-name venues that no longer exist.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s. American consumers were gripped by fast food, mailorder catalogs, and mall culture. You didn’t come of age until you prowled the local shopping centers for Orange Julius and Mrs. Field’s cookies. You went to the movie theater on Friday nights and hung out at Dairy Queen afterwards. Thus, we reminisce — ghost stories of ghost stores — about Kmart, Circuit City, Wherehouse Music, and Blockbuster. I miss the big toy giants like the Disney Store, KB Toys and Toys R Us. I have warm memories of the Southern California Mexican fast food chain Naugles (which, recently resurrected), Souplantation, and Gemco.

One of the most curious chain stores I vaguely recall as a youth was called Best. Not Best Buy, but Best. What an efficient and apt encapsulation. Like when James Jebbia titled his skate shop Supreme - it acted as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Founded in the 1950s when mail order catalog business was the e-commerce of the day (see: Sears), Sydney and Frances Lewis opened a physical showroom in Richmond, Virginia so that consumers could actually touch and see the product. The Best in my town was similar to the 168 others nationwide. It was a sprawling, white space that staged houseware in various settings with a baby section at the finish line.

You’d take note of what you wanted, submit your order to a cashier at the end of your journey, and wait by a conveyor belt by the store’s exit for your items to deliver. From a second-floor warehouse portal, cardboard boxes of all shapes and sizes would tumble down like baggage claim. It wasn’t unlike a modern day IKEA, except I wanna say that the offerings were more diverse than furniture - including electronics and jewelry.

Best eventually liquidated after filing for bankruptcy - twice - by the late 1990s. Whenever I play the “What happened to that store?” game, people hardly remember it. Perhaps more tragically, they don’t remember Best’s contributions to the arts. As savvy as the Lewises were at business, they were prolific art collectors. Legend has it that the family often traded shop merchandise for contemporary pieces by some of the modern masters. Today, their collection of Art Nouveau and Art Deco furniture is on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

But if anyone remembers Best, it’s design students. Best is celebrated in architecture circles for having pushed the boundaries of experiential buildouts. In the 1970s, the Lewises collaborated with the environmental artist James Wines on nine Best locations that challenged and deconstructed big-box retail aesthetic. They’d make the avant-garde Gentle Monster flagships of today look like office supplies stores!

Perhaps the most iconic of the SITE stores was the Houston location, “Indeterminate Facade,” which was built in 1975 and appeared in more books on 20th century architecture than any other modern structure.

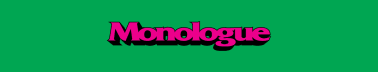

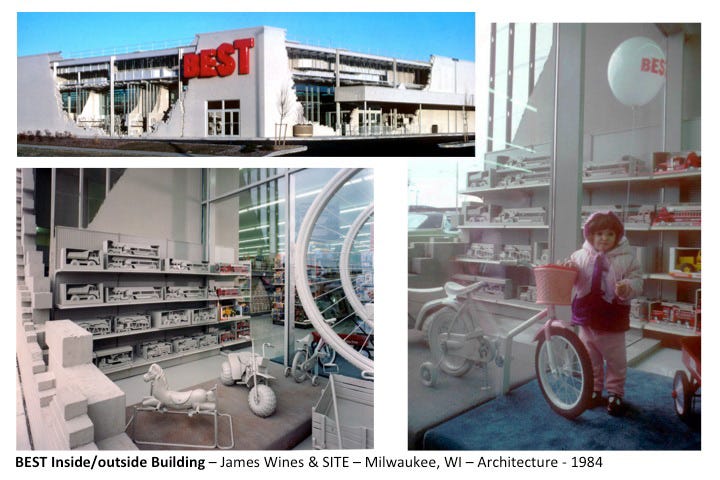

In the same vein, the “Inside/Outside” buildout in Milwaukee, Wisconsin was a literal cross-section of a Best store that cut directly through the merchandise.

(You may pick up on the inspiration for The Hundreds Santa Monica (for those who remember that ghost store!))

My favorite of all the James Wines Best designs was the Peeling Facade in Richmond:

Sacramento’s “Notch Facade” had a corner that the staff would “break out” at the start of every day.

And Richmond’s “Forest of the Facade” realized a forest growing through a Best store.

I can’t even imagine the structural engineering it took to articulate the “Tilted” Best store in Maryland…

There were even more. Research all of them as well as James Wines’ further architectural work. It blows my mind how ingenious and imaginative this mail order catalog business was half a century ago. The headlines would go viral if somebody tried this today and yet, Best is buried at the bottom of the Internet. Sometimes the most innovative design isn’t waiting for us in the future - it’s already far behind us.

Reminds me of the thought put into the facades of luxury stores in Ginza, Tokyo. Sad (to an old guy like me) that we probably won't be seeing this sort of ingenuity anymore with the decline of brick-and-mortar businesses being as profitable as they once were. I hope I'm wrong.