I recently read this story about a chaplain who reflected on what he’s learned from counseling thousands of dying patients. It’s a really beautiful piece; you should read it. One of the anecdotes that stuck with me was about an unhoused musician who “sings about a home he never had.”

I wish we’d gotten to hear that song. It could have been a universal anthem. Even if you’re fortunate enough to have physical shelter, many of us feel without a home these days, moving around to seek better job opportunities or more affordable lifestyles. But it’s not just in the literal sense. We’re spiritually lost, politically homeless. It’s become more difficult to grasp meaning in a transitional season.

As definitions soften, when values shift, if life loses purpose and structure — It’s harder to establish who we are. I’ve said this before, but most sectors, companies, brands, and individuals are weathering an identity crisis. It’s a time of upheaval and awakening, but it’s also a scary time for those of us who sit between roles and communities (or outside of them altogether). It’s fraught, uncomfortable, and at times, hopeless.

This week, The Hundreds released a collaborative collection with the record label, Flatspot Records. I love Flatspot for their artist curation and for the caliber and quality of their work. I also appreciate them for spotlighting bands that transcend systemic patterns, due to their race, gender, geography, opinions, and the resulting music that comes from being a minority in a minority subculture. Some of the hardcore label’s biggest bands can’t even neatly be comparmentalized as “hardcore.” This is altogether important for a community that has been a sanctuary for generations of young people who didn’t fit within the broader picture. As hardcore has gone more mainstream (thanks to bands like Turnstile), the scene is finding new and creative ways to catch those who are falling into the cracks.

When Ricky Singh, co-owner of Flatspot Records, learned that I hailed from Maryland, he suggested that we throw the project’s release party in Baltimore, since that’s where one of the bands we worked with — End It — was from. This would be my first time returning to my hometown since I was a child. I was born in Westminster, Maryland in 1980 and spent my first years in the middle-class, suburban town of Ellicott City. But we were uprooted once again. My family eventually found our way to Fountain Valley, California, then the Inland Empire. I’ve now lived in Los Angeles for more than half of my life.

I can’t quite call Maryland home, but it’s forever been a part of me. Like, I’ve always felt a kinship with anyone in an Orioles cap (my favorite sports team as a child alongside the Baltimore Colts)! Every time I’m asked to declare my birthplace on a form, I’m reminded that my roots are buried somewhere in the East Coast, in a ghost life that never materialized. It’s like when I found out that Tupac was also from Baltimore, enrolled in the School for the Arts where he studied acting, poetry, jazz and ballet. Who was this version of Tupac and where would his path have taken him if he had stayed the course? It’s funny to think of how many stories and identities and multiverses an individual can have. How fluid and complex we can be if we let life happen to us.

On our way from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore, David and I veered a bit off-course to visit my childhood home in Ellicott City. Down the 295, we went from the newness of the city’s commercial buildings to the rolling green pastures and forested hills of the Maryland suburbs. Ellicott City was built on seven hills to be exact, and has historically been a milling town, “home to a population of poverty-class and working-class Appalachian and Southern migrants who came north looking for jobs.” After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the borders for Asian immigrants, my parents set up camp here in the early 1980s. Today, around 12,000 Korean-Americans live in this community, accounting for almost a quarter of the population.

It almost seemed like we were lost when we got off the highway exit. Although I’ve heard Ellicott City is home to an H Mart and every chain restaurant you can think of, I saw nothing but nothing. The bricklaid shopping centers were pristine and the parking lots half-full. Not a grass blade out of place. In some ways, it reminded me of the quieter pockets of Irvine or the Bay, with older Asian neighbors stretching on corners amidst mid-day walks. I was trying to imagine my immigrant parents moving from rural South Korea to a region like this forty years ago. What did they buy at the grocery store to prepare for meals? Where did they go to make friends and socialize?

As we crested the hill in the rental, we happened upon parents gathering at the school bus stop, ready to alleviate their children of bookbags and usher them into afternoon activities. It was straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting. I envisioned the kids baking warm apple pies and setting them on the windowsill to cool, before saying grace and carving up chicken pot pie. Of course, they probably sat on iPads and watched Dude Perfect for 4 hours while their parents leafed through Facebook Marketplace. But for as long as I can remember, I’ve daydreamt about an All-American upbringing, the sort that I read about in Judy Blume books and watched in John Hughes movies. Maybe those phantom memoirs were planted and blossoming here.

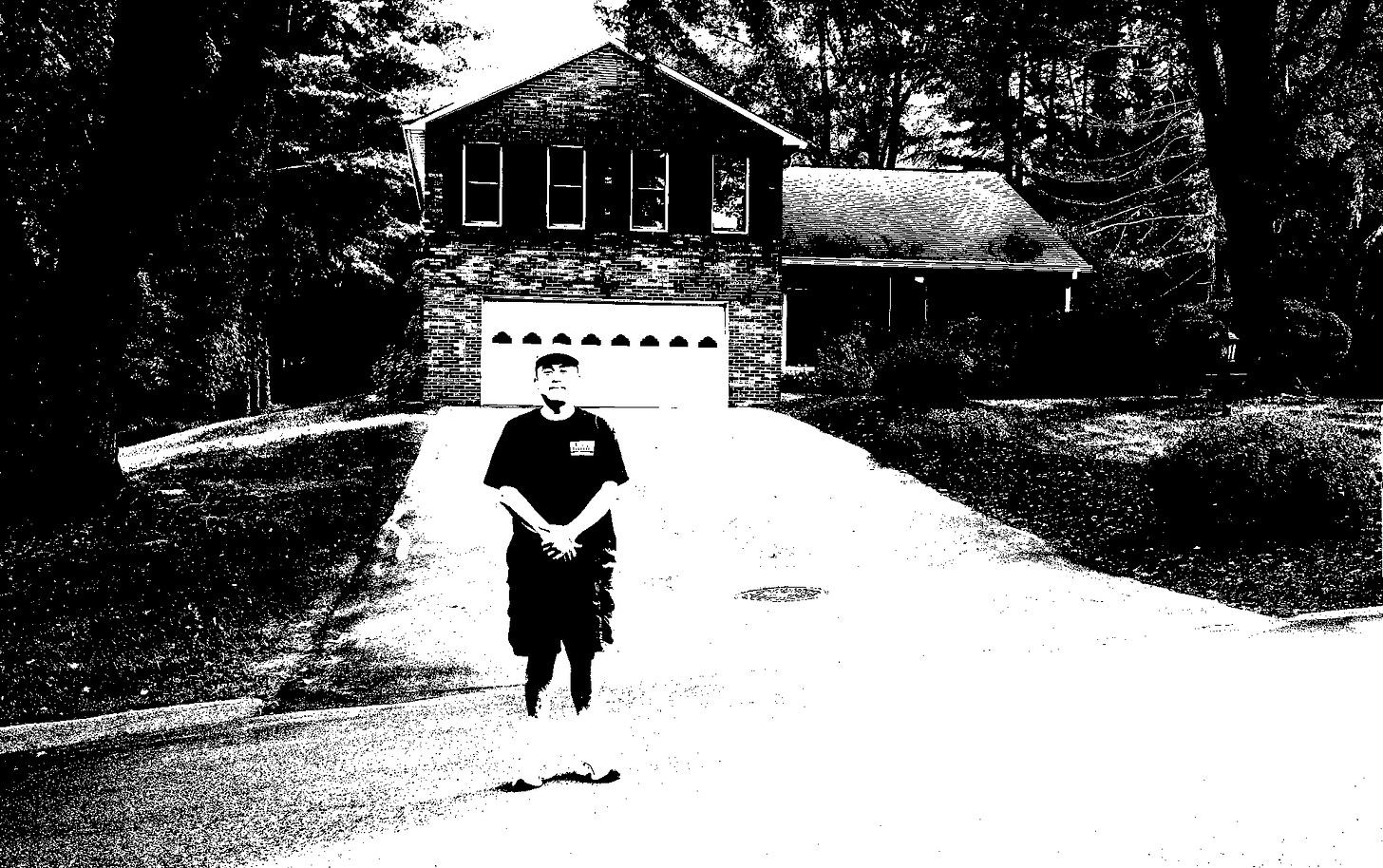

My childhood home looked just as I remembered it. Sometimes I return to prior residences and note how big or small they feel in the context of my new life. But this house was as if I’d drawn it from memory — as if I’d lived here all along — with grey-blue siding and a sloped backyard that disappeared into the umbrage of a heavy treeline. I was a little self-conscious to get out of the car. The streets were sweeping and empty outside of parents walking their children home. Neighbors sat on their porches, monitoring the subtle movements of the neighborhood.

David shot a portrait of me in the street in front of the house. I’m sure the locals wondered who this grown Asian man was and why he was dressed like a toddler and more than anything, why he was so particularly interested in this building. I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and listened. It was so quiet that you could hear the trees. The leaves clapped in soft applause. The insects (or were they birds?) chirped in a way I guessed would get annoying with time. Not right now, though. It was musical.

I texted my brothers and my parents. They helped me remember.

“We used to kick the soccer ball up that backyard hill.”

”Your room was right above the garage, behind those four windows.”

”Mom used to be so jealous of the other neighbors for being able to afford an automatic garage. She had to close ours by hand.”

Some of these memories sprang forth instantly. Others seemed torn from a classic novel. This was my story but it wasn’t. This was my home but it was also a stranger’s. I suddenly felt out of place and disoriented. It was time to leave.

That night, we put on a hardcore show in Baltimore with Flatspot for hundreds of our shared community. Everyone was so cool, generous, and kind. The next morning, we met some friends for Turkish breakfast and they invited us to their warehouse, which was situated in the neighborhood where they shot The Wire. I finally got to pay a visit to the sneaker boutique, Major, in Georgetown, one of our earliets partners. Duk-Ki, the owner, was surprised to see us and regaled us with old sneakerhead stories.

I learned a lot about Baltimore: how you don’t really have to stop at red lights, which neighborhoods are getting gentrified, where to order Thai food from at 1 in the morning. By the end of my stay, I pictured myself living there. I do this every time I travel, no matter where I am in the world. Sometimes, it works effortlessly. Most of the time, there’s something in the way. Baltimore fit like a glove.

Back in Santa Monica, it’s 75 degrees, sunny, and not a cloud in the sky this afternoon. I’m glad my parents bravely made the westward haul to California nearly half a century ago and I was happy to return home after an eventful week. But it’s nice to know that somewhere out in Howard County, Maryland, there’s another Bobby who’s faring well and going to hardcore shows and writing a rich and abundant story in a different home. A home I never had.

Another verbal journey into your world that was like a visual movie, thank you.